From Passus V of Piers Plowman; the speaker is Repentance, who has just heard confessions from personifications of the seven deadly sins:

"Have mercy in thi mynde, and with thi mouth biseche it,

For [his] mercy is moore than alle hise othere werkes -

Misericordia eius super omnia opera eius, &c -

And al the wikkednesse in this world that man myghte werche or thynke

Nis na moore to the mercy of God than in[middes] the see a gleede:

Omnis iniquitas quantum ad misericordiam Dei est quasi scintilla in medio maris...

And thanne hadde Repentaunce ruthe and redde hem alle to knele.

"For I shal biseche for alle synfulle Oure Saveour of grace

To amenden us of oure mysdedes and do mercy to us alle.

Now God,' quod he, "that of Thi goodnesse gonne the world make,

And of naught madest aught and man moost lik to thiselve,

And sithen suffredest hym to synne, a siknesse to us alle -

And al for the beste, as I bileve, whatevere the Book telleth:

O felix culpa! O necessarium peccutum Ade!

For thorugh that synne thi sone sent was to this erthe

And bicam man of a maide mankynde to save -

And madest Thiself with Thi sone us synfulle yliche:

Faciamus hominem ad imaginem et similitudinem nostram; Et anoi

Qui manet in caritate, in Deo manet, et Deus in eo;

And siththe with Thi selve sone in oure sute deidest

On Good Fryday for mannes sake at ful tyme of the day;

Ther Thiself ne Thi sone no sorwe in deeth feledest,

But in oure secte was the sorwe, and Thi sone it ladde:

Captivum duxit captivitatem.

The sonne for sorwe therof lees sight for a tyme

Aboute mydday whan moost light is and meel-tyme of seintes -

Feddest tho with Thi fresshe blood oure forefadres in derknesse:

Populus qui ambulabat in tenebris vidit lucem mugnam.

And the light that lepe out of Thee, Lucifer it blente,

And blewe alle Thi blessed into the blisse of Paradys!

"The thridde day therafter Thow yedest in oure sute:

A synful Marie The seigh er Seynte Marie Thi dame,

And al to solace synfulle Thow suffredest it so were -

Non veni vocare iustos set peccatores ad penitenciam.

"And al that Marc hath ymaad, Mathew, Johan and Lucas

Of Thyne doughtiest dedes was doon in oure armes:

Verbum caro factum est et hubitavit in nobis.

And by so muche it semeth the sikerer we mowe

Bidde and biseche, if it be Thi wille

That art oure fader and oure brother - be merciable to us,

And have ruthe on thise ribaudes that repenten hem soore

That evere thei wrathed Thee in this world, in word, thought or dede!'

Thanne hente Hope an horn of Deus tu conversus vivificabis nos

And blew it with Beati quorum remisse sunt iniquitate

That alle Seintes in hevene songen at ones

"Homines et iumenta salvabis, quemadmodum multiplicasti misericordiam tuam."

A thousand of men tho thrungen togideres,

Cride upward to Crist and to his clene moder

To have grace to go seke Truthe - God leve that they moten!

Easier:

"Have mercy in thy mind, and with thy mouth beseech it,

For his mercy is greater than all his other works -

His mercy is over all his works.

And all the wickedness in this world that man may do or think

Is no more, compared to the mercy of God, than a spark of fire in the midst of the sea:

All sins are like a little spark in the middle of the sea, compared to the mercy of God...

And then Repentance had pity, and prayed them all to kneel.

"For I shall beseech our Saviour for grace for all sinners

To amend us of our misdeeds and show mercy to us all.

Now God," quoth he, "that of thy goodness did the world make,

And of nothing madest everything, and man the most like thyself,

And then suffredest him to sin, a sickness to us all -

And all for the best, as I believe, all as the Book telleth:

O happy fault! O necessary sin of Adam!

For through that sin thy son sent was to this earth

And became man of a maid, mankind to save -

And madest thyself with thy son like us sinners:

Let us make man in our own image and likeness; And also:

Whoever lives in love, lives in God, and God in him.

And then [thou] with thine own son in our suit died

On Good Friday for man's sake at full time of the day;

There thyself nor thy son no sorrow felt in death,

But among our sort was the sorrow, and thy son led it forth:

He led captivity captive.

The sun for sorrow thereof lost sight for a time

About midday, when most light is, and meal-time of saintes -

Feddest thou with thy fresh blood our forefathers in darkness:

The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light.

And the light that leapt out of thee, Lucifer it blinded,

And blew all thy blessed into the bliss of Paradise!

"The third day thereafter thou went in our suit:

A sinful Mary saw thee before Saint Mary thy mother,

And all to solace the synful thou sufferedest it to be so -

I did not come to call the just but sinners to repentance.

"And all that Mark hath made, Matthew, John and Lucas

Of thine doughtiest deeds was done in our arms:

The word became flesh and dwelt among us.

And by so much it seemeth the more surely we may

Bid and beseech, if it be thy will

Thou that art our father and our brother - be merciful to us,

And have ruth on these sinners that repent themselves sorely

That ever they wrathed thee in this world, in word, thought or deed!'

Then took Hope an horn of Turn, O God, and quicken us

And blew it with Blessed are those whose sins are forgiven.

That all saints in heaven sung at once

"Thou wilt save both man and beast; how thou hast multiplied thy mercy!"

A thousand of men then thronged together,

Cried upward to Christ and to his pure mother

To have grace to go seek Truth - God grant that they might!

▼

Saturday, 30 April 2011

Friday, 29 April 2011

O Perfect Love

OK, maybe I have one thing more to say about the Royal Wedding. But it's just this: a wedding hymn. (Do read the charming story of how it came to be written).

O perfect Love, all human thought transcending,

Lowly we kneel in prayer before Thy throne,

That theirs may be the love which knows no ending,

Whom Thou forevermore dost join in one.

O perfect Life, be Thou their full assurance,

Of tender charity and steadfast faith,

Of patient hope and quiet, brave endurance,

With childlike trust that fears nor pain nor death.

Grant them the joy which brightens earthly sorrow;

Grant them the peace which calms all earthly strife,

And to life’s day the glorious unknown morrow

That dawns upon eternal love and life.

Hear us, O Father, gracious and forgiving,

Through Jesus Christ, Thy coeternal Word,

Who, with the Holy Ghost, by all things living

Now and to endless ages art adored.

O perfect Love, all human thought transcending,

Lowly we kneel in prayer before Thy throne,

That theirs may be the love which knows no ending,

Whom Thou forevermore dost join in one.

O perfect Life, be Thou their full assurance,

Of tender charity and steadfast faith,

Of patient hope and quiet, brave endurance,

With childlike trust that fears nor pain nor death.

Grant them the joy which brightens earthly sorrow;

Grant them the peace which calms all earthly strife,

And to life’s day the glorious unknown morrow

That dawns upon eternal love and life.

Hear us, O Father, gracious and forgiving,

Through Jesus Christ, Thy coeternal Word,

Who, with the Holy Ghost, by all things living

Now and to endless ages art adored.

Thursday, 28 April 2011

A Medieval Love Poem: When the Nightingale Sings

I've posted this before, but it's April, and it's a great poem, so I'm posting it again.

When the nyhtegale singes,

The wodes waxen grene,

Lef ant gras ant blosme springes

In Averyl, Y wene;

Ant love is to myn herte gon

With one spere so kene,

Nyht ant day my blod hit drynkes

Myn herte deth me tene.

Ich have loved al this yer

That Y may love na more;

Ich have siked moni syk,

Lemmon, for thin ore,

Me nis love neuer the ner,

Ant that me reweth sore;

Suete lemmon, thench on me,

Ich have loved the yore.

Suete lemmon, Y preye thee,

Of love one speche;

Whil Y lyve in world so wyde

Other nulle Y seche.

With thy love, my suete leof,

My blis thou mihtes eche;

A suete cos of thy mouth

Mihte be my leche.

Suete lemmon, Y preye thee

Of a love-bene:

Yef thou me lovest, ase men says,

Lemmon, as I wene,

Ant yef hit thi wille be,

Thou loke that hit be sene;

So muchel Y thenke vpon the

That al y waxe grene.

Bituene Lyncolne ant Lyndeseye,

Northamptoun ant Lounde,

Ne wot I non so fayr a may,

As y go fore ybounde.

Suete lemmon, Y preye the

Thou lovie me a stounde;

Y wole mone my song

On wham that hit ys on ylong.

This is one of the 'Harley lyrics', a group of poems preserved in British Library, Harley MS 2253. The manuscript was made early in the fourteenth century in the West Midlands, and contains works in English, Latin and French; the English poems are some of the best-known Middle English lyrics, and include several other springtime poems, among them 'Lenten ys come with love to toune' and 'Bytuene Mersh ant Averil'.

Men and women gathering flowers in April (BL Yates Thompson 3, f. 4)

A translation (lemman = sweetheart, darling):

When the nightingale sings

The woods grow green,

Leaf and grass and blossom spring

In April, I believe.

And love is to my heart gone

With a spear so keen,

Night and day my blood it drinks

My heart causes me pain.

I have loved all this year

Such that I may love no more;

I have sighed many sighs,

Lemman, for your pity.

To me love is never any nearer,

And that I sorely regret.

Sweet lemman, think on me -

I have loved you long.

Sweet lemman, I pray you

Give me one love-speech.

While I live in the world so wide

None other will I seek!

With your love, my sweet beloved,

My bliss you might increase;

A sweet kiss from your mouth

Would be my cure.

Sweet lemman, I pray you

For a gift of love.

If you love me, as men say,

And lemman, as I believe,

If it be your will

Make it to be seen!

So much I think on you

That I grow green. [like the woods!]

Between Lincoln and Lindsey,

Northampton and Lound

I know of no maid so fair

As the one who holds me in bondage.

Sweet lemman, I pray you,

Love me a little while!

I will sing my song

To the one to whom it belongs.

Women picking flowers, in a calendar for April (BL Royal 2 B VII, f. 74v)

A Virtual Visit to Wye

Wye is a pretty village on the road between Ashford and Canterbury, a pleasant and prosperous area where Kent is at its most Garden-of-England-ish. I visited last week on Maundy Thursday, when everything was blossom and sunlight.

Wye is a pretty village on the road between Ashford and Canterbury, a pleasant and prosperous area where Kent is at its most Garden-of-England-ish. I visited last week on Maundy Thursday, when everything was blossom and sunlight.

For once the church was not the primary purpose of my visit, but I went there anyway. It had plenty of blossom too:

For once the church was not the primary purpose of my visit, but I went there anyway. It had plenty of blossom too: Inside, it's a church of two parts: a spacious, light-filled medieval nave, and a dark panelled chancel (a tower collapsed in the seventeenth century, and this section of the church had to be rebuilt).

Inside, it's a church of two parts: a spacious, light-filled medieval nave, and a dark panelled chancel (a tower collapsed in the seventeenth century, and this section of the church had to be rebuilt). The darkness of this photo is entirely true to life:

The darkness of this photo is entirely true to life: You can see that above the panelling are numerous memorials, of different periods, some very interesting. All church monuments are interesting - but some touch the heart more than others. Here, for instance, is a memorial to female friendship:

You can see that above the panelling are numerous memorials, of different periods, some very interesting. All church monuments are interesting - but some touch the heart more than others. Here, for instance, is a memorial to female friendship: In a vault near this place lie interred

In a vault near this place lie interredThe Bodies of Agnes & Mary Johnson

The former of whome died January 3rd 1763 aged 48

The latter August 12 1767 Aged 48

They were Daughters & Coheiresses of

John Johnson Esq of Wye in Kent

And of Mary Johnson, descended from

Sir Robert Moyle of Buckwell.

Their days were imbittered by various evils

Their conduct proves that true Christian resignation

May palliate the heaviest afflictions.

This stone was erected

In remembrance of a friendship which death alone could end

By Susanna and Penelope Woodyers

Executrixes to Mrs Mary Johnson

All memorials to clergymen make me think of Charlotte Yonge, and this one to the Rev. Robert Billing would have touched a chord with her. "He died suddenly in Canterbury Cathedral, having just risen from prayer." "Watch therefore, for ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son of Man cometh."

All memorials to clergymen make me think of Charlotte Yonge, and this one to the Rev. Robert Billing would have touched a chord with her. "He died suddenly in Canterbury Cathedral, having just risen from prayer." "Watch therefore, for ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son of Man cometh."

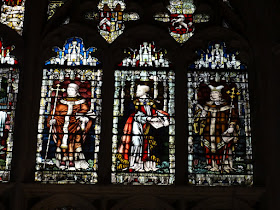

The west window only dates from 1951, and it's imposing yet gracious. It depicts Christ in Majesty, with the church's patrons, St Gregory the Great (holding a book of Gregorian chant) and St Martin of Tours. Above that are instruments of the Passion and a variety of cherub heads:

The west window only dates from 1951, and it's imposing yet gracious. It depicts Christ in Majesty, with the church's patrons, St Gregory the Great (holding a book of Gregorian chant) and St Martin of Tours. Above that are instruments of the Passion and a variety of cherub heads:The lower panels are dedicated to one of Wye's most successful native sons, John Kempe, Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1447 he founded a college next to the church, which closed, sadly, just two years ago. If you walk past the beautiful building which used to be the college, you can catch a glimpse of the quad (doubtless such an Oxbridge-like college was a home from home for Kempe, a Merton College man; oh, these modern pretenders!).

Here's Kempe, bathed in sunlight:

At different times he was bishop or archbishop of Rochester, Chichester, London, York and Canterbury, and a Cardinal, and Lord Chancellor of England. This seems like more titles than one man could need, but there you are. The wheat-sheaf behind him alludes to his family arms; the blue crest is that of Canterbury and the one below of Rochester. My heraldry fails me with the others.

Delightfully, the artist has surrounded Kempe with some typical scenes of Kentish rural life. On one side, hop-picking, some oasthouses, and sheep:

And on the other, an orchard (with a view of Wye itself in the distance) - the Garden of England, remember! - and farming. I wonder if this is the only church window in the country which depicts a tractor. The crown on the hillside is a local landmark, a chalk design carved in 1902 by students of Wye College to commemorate the coronation of Edward VII:

The entwining botanical surround and the pheasant, squirrel, rabbit and other birds are just lovely.

And back out into the churchyard, where Charlotte Yonge again came to mind when I saw this blossom-bedecked tombstone:

Ethelred is the name of the heroine of The Daisy Chain, and it always struck me as an odd choice for a woman's name, because I associate it with the various Anglo-Saxon kings named Æthelred; I don't think it was an Anglo-Saxon female name. However, clearly Yonge didn't make it up, since Ethelred Kirby, 'sister of the above', was born a good half century before The Daisy Chain. Not sure what happened there.

Ethelred is the name of the heroine of The Daisy Chain, and it always struck me as an odd choice for a woman's name, because I associate it with the various Anglo-Saxon kings named Æthelred; I don't think it was an Anglo-Saxon female name. However, clearly Yonge didn't make it up, since Ethelred Kirby, 'sister of the above', was born a good half century before The Daisy Chain. Not sure what happened there.

Wednesday, 27 April 2011

The Stained Glass of Canterbury, Modern Edition

I went to Canterbury last week, and slipped into the cathedral in search of quiet - and also of medieval people. Canterbury has some of the finest medieval glass in the country (probably in the world) and so it seems a little perverse to come away only talking about the modern examples; but perhaps it can be forgiven in a reception theory kind of way? I promise that I did pay due tribute to the real medieval stuff, and take photos of that too, but I'll only deal with the modern here. If you would like to know more about the medieval glass of Canterbury, and the admirable work being done to conserve it, go here and here.

Anyway. I had just written last week's post about Anselm when I visited the cathedral, and so I went to the chapel dedicated to him, which looks like this:

The altar was only installed in 2006. The chapel, which suffered bomb damage in World War II, has a modern window in commemoration of Anselm, which was very bright on that sunny day, and also very red.

The altar was only installed in 2006. The chapel, which suffered bomb damage in World War II, has a modern window in commemoration of Anselm, which was very bright on that sunny day, and also very red.

Very red. This window dates from 1959, as I think you can rather tell.

Anselm is flanked by his predecessor Lanfranc (in green) and successor Baldwin (in white), and either side of them are two kings, Henry I (as at Norwich, though depicted as much older here!) and William Rufus.

Anselm is flanked by his predecessor Lanfranc (in green) and successor Baldwin (in white), and either side of them are two kings, Henry I (as at Norwich, though depicted as much older here!) and William Rufus.

William Rufus, complete with beard, helpfully contributes to the whole red theme:

He and Anselm did not get on at all - but this is reconciliation in glass.

In the chapter house, off the cloisters, there are two windows depicting figures from the history of Canterbury down to the days of Queen Victoria. Here are King Ethelbert of Kent and Queen Bertha, with Augustine:

Bertha's drapery is rather pretty; Ethelbert has the cross-gartered legs always attributed to Anglo-Saxons by nineteenth-century artists!

Here are the three archbishops who concerned me last week: Alphege, rather gruesomely holding the bones with which he was pelted by his captors; Lanfranc, planning the building of the new cathedral; and Anselm, looking oddly like a well-fed Protestant divine of the seventeenth century.

Thomas Becket, even more stout than Anselm, and with a fearsome-looking sword.

I puzzled for a good while about the next few scenes (these are from another window in the chapter house). This is Augustine and the baptism of Ethelbert:

I think the man being martyred in the picture below must be Alphege, since the weapons look like bones. But if so the Danes don't look much like your usual depiction of Vikings; for one thing, they're wearing striking jewel-bright clothes:

Next, I assume Becket's murder is on the far left here, followed by the king doing penance for his death, and the translation of his body:

But what's going on in this one? Perhaps the far right depicts the death of Simon Sudbury, yet another Archbishop of Canterbury who met a violent end, this time at the hands of the Peasants' Revolt. That's just a guess, though.

I don't recognise the marriage or the middle scene.

But finally, on the outside of the cathedral, among the statues, Anselm again:

And in place of honour, flanking the door through which the tourists were streaming, Ethelbert and Bertha:

Matronly and fair.

Anyway. I had just written last week's post about Anselm when I visited the cathedral, and so I went to the chapel dedicated to him, which looks like this:

The altar was only installed in 2006. The chapel, which suffered bomb damage in World War II, has a modern window in commemoration of Anselm, which was very bright on that sunny day, and also very red.

The altar was only installed in 2006. The chapel, which suffered bomb damage in World War II, has a modern window in commemoration of Anselm, which was very bright on that sunny day, and also very red.

Very red. This window dates from 1959, as I think you can rather tell.

Anselm is flanked by his predecessor Lanfranc (in green) and successor Baldwin (in white), and either side of them are two kings, Henry I (as at Norwich, though depicted as much older here!) and William Rufus.

Anselm is flanked by his predecessor Lanfranc (in green) and successor Baldwin (in white), and either side of them are two kings, Henry I (as at Norwich, though depicted as much older here!) and William Rufus.

William Rufus, complete with beard, helpfully contributes to the whole red theme:

He and Anselm did not get on at all - but this is reconciliation in glass.

In the chapter house, off the cloisters, there are two windows depicting figures from the history of Canterbury down to the days of Queen Victoria. Here are King Ethelbert of Kent and Queen Bertha, with Augustine:

Bertha's drapery is rather pretty; Ethelbert has the cross-gartered legs always attributed to Anglo-Saxons by nineteenth-century artists!

Here are the three archbishops who concerned me last week: Alphege, rather gruesomely holding the bones with which he was pelted by his captors; Lanfranc, planning the building of the new cathedral; and Anselm, looking oddly like a well-fed Protestant divine of the seventeenth century.

Thomas Becket, even more stout than Anselm, and with a fearsome-looking sword.

I puzzled for a good while about the next few scenes (these are from another window in the chapter house). This is Augustine and the baptism of Ethelbert:

I think the man being martyred in the picture below must be Alphege, since the weapons look like bones. But if so the Danes don't look much like your usual depiction of Vikings; for one thing, they're wearing striking jewel-bright clothes:

Next, I assume Becket's murder is on the far left here, followed by the king doing penance for his death, and the translation of his body:

But what's going on in this one? Perhaps the far right depicts the death of Simon Sudbury, yet another Archbishop of Canterbury who met a violent end, this time at the hands of the Peasants' Revolt. That's just a guess, though.

I don't recognise the marriage or the middle scene.

But finally, on the outside of the cathedral, among the statues, Anselm again:

And in place of honour, flanking the door through which the tourists were streaming, Ethelbert and Bertha:

Matronly and fair.

That we may bring the same to good effect

The Collect for Easter, from the Book of Common Prayer - a prayer for those of us who made good resolutions on Easter Sunday, and are now in need of some help in carrying them out:

Almighty God, who through thine only-begotten Son Jesus Christ hast overcome death, and opened unto us the gate of everlasting life; We humbly beseech thee, that, as by thy special grace preventing us thou dost put into our minds good desires, so by thy continual help we may bring the same to good effect; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end.

(preventing definition 4)

Almighty God, who through thine only-begotten Son Jesus Christ hast overcome death, and opened unto us the gate of everlasting life; We humbly beseech thee, that, as by thy special grace preventing us thou dost put into our minds good desires, so by thy continual help we may bring the same to good effect; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end.

(preventing definition 4)

Tuesday, 26 April 2011

The Christian Valkyrie

I'm a massive fan of the Victorian novelist Charlotte Yonge, and have been beguiling my Easter holiday with her monumental 1873 novel The Pillars of the House - so very long, but so very lovable! She's hugely under-rated, hardly read today (though once immensely popular) and academics seem only interested in her as far as they can talk about gender stereotyping and religious extremism. I'm only an amateur Victorianist, but in my opinion she's a truly great novelist of a particular stamp: she has her limitations, but she has an extremely subtle and sensitive understanding of character and social relationships, which are worked out in her novels with a complexity surpassing many of her contemporaries. If Jane Austen had been born a Victorian, and thus had a taste which leaned more towards hugely long novels about redemptive suffering than to elegant eighteenth-century pen-portraits, she would have been like Charlotte Yonge.

Anyway, one of Yonge's most endearing features is her enthusiastic interest in history (she wrote a large number of historical novels, though personally I prefer her contemporary fiction) and to me one of the sideline pleasures of her work is a useful insight into a certain kind of Victorian medievalism. She wrote an intelligent novel, aimed at young children, about the Dukes of Normandy; her modern characters read the Old English Boethius attributed to Alfred the Great. She compares the experience of one hero to a famous episode in the conversion of Iceland, and her understanding of Christian knighthood as a pattern for modern life is a theme which runs through all her work. And then there's this, which I read this morning, and find very striking. It's from a sermon given by one of the main characters in The Pillars of the House after he, and several of his brothers, have been involved in a fatal boating accident. One of his brothers has been killed, and the clerical brother, preaching at the funeral, speaks thus:

'"One shall be taken and another left. They say unto Him, Where, Lord?" Yes. Strange, startling, arbitrary, as seem often the calls to the soldiers in Christ's army, each is at its true time, for the choice is made in Love...

[The vicar describes] the picture of the serried ranks, standing fast in one army, warring as one band against darkness, foulness, cruelty, and all other evils, each fighting his own battle in private, yet even thus striking as much for the cause as for himself. So they stood, soldiers in a campaign, aware that any moment might snatch them out of the ranks, yet also aware that not one would be taken save at the right moment when his warfare had come to the crisis. Our forefathers of old believed in glorious maidens who floated over the battle-field as choosers of the slain, and bore hero-spirits away to the Home of Triumph in chariots of light, to dwell among the brave. Like them we believe in the Triumphant Home, where dwell the brave who have stood steadfast in faith, joyful through hope, rooted in charity, bright in purity, dashing down the arrows of temptation that glint against their armour. Like them, we believe in a Chooser of the slain, bearing us, one by one, from our several posts, with longer or shorter warning, exactly when our warfare is accomplished, our individual battle is, or ought to be, won.'

vol. ii, p.404.

'chooser of the slain' is a literal translation of the Old Norse valkyrja and its Old English cognate, wælcyrie, the female spirits who appeared above the field of battle and claimed the greatest warriors for death and for Odin. The discussion of the Christian life as a battle - particularly a private battle against one's own personal temptations - is very characteristic of Yonge; it finds its fullest expression in her most famous novel, The Heir of Redclyffe. This picture of God-as-valkyrie is, however, an unusual and rather elegant bit of syncretism.

Image: Arthur Rackham's vision of Brynhildr, the most famous valkyrie of them all.

Monday, 25 April 2011

Gather gladness from the skies

An uncharacteristically straightforward Easter poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins; this reads like he was channelling Robert Herrick or something. Nice, though.

Easter

Break the box and shed the nard;

Stop not now to count the cost;

Hither bring pearl, opal, sard;

Reck not what the poor have lost;

Upon Christ throw all away:

Know ye, this is Easter Day.

Build His church and deck His shrine;

Empty though it be on earth;

Ye have kept your choicest wine—

Let it flow for heavenly mirth;

Pluck the harp and breathe the horn:

Know ye not ‘tis Easter morn?

Gather gladness from the skies;

Take a lesson from the ground;

Flowers do ope their heavenward eyes

And a Spring-time joy have found;

Earth throws Winter’s robes away,

Decks herself for Easter Day.

Beauty now for ashes wear,

Perfumes for the garb of woe.

Chaplets for disheveled hair,

Dances for sad footsteps slow;

Open wide your hearts that they

Let in joy this Easter Day.

Seek God’s house in happy throng;

Crowded let His table be;

Mingle praises, prayer and song,

Singing to the Trinity.

Henceforth let your souls alway

Make each morn an Easter Day.

Easter

Break the box and shed the nard;

Stop not now to count the cost;

Hither bring pearl, opal, sard;

Reck not what the poor have lost;

Upon Christ throw all away:

Know ye, this is Easter Day.

Build His church and deck His shrine;

Empty though it be on earth;

Ye have kept your choicest wine—

Let it flow for heavenly mirth;

Pluck the harp and breathe the horn:

Know ye not ‘tis Easter morn?

Gather gladness from the skies;

Take a lesson from the ground;

Flowers do ope their heavenward eyes

And a Spring-time joy have found;

Earth throws Winter’s robes away,

Decks herself for Easter Day.

Beauty now for ashes wear,

Perfumes for the garb of woe.

Chaplets for disheveled hair,

Dances for sad footsteps slow;

Open wide your hearts that they

Let in joy this Easter Day.

Seek God’s house in happy throng;

Crowded let His table be;

Mingle praises, prayer and song,

Singing to the Trinity.

Henceforth let your souls alway

Make each morn an Easter Day.

Sunday, 24 April 2011

The sun that waxed all pale now shines bright

Happy Easter! Here's a hymn of the Resurrection by William Dunbar, a wonderful Scottish poet who died c.1520. The language of this fantastic poem is much more easily comprehensible than the spelling makes it look - just read it aloud!

Done is a battell on the dragon blak;

Our campioun Chryst coufoundit hes his force:

The yettis of hell ar brokin with a crak,

The signe triumphall rasit is of the croce,

The divillis trymmillis with hiddous voce,

The saulis ar borrowit and to the bliss can go,

Chryst with his blud our ransonis dois indoce:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

Dungin is the deidly dragon Lucifer,

The crewall serpent with the mortall stang,

The auld keen tegir with his teith on char

Quhilk in a wait hes lyne for us so lang

Thinking to grip us in his clowis strang:

The merciful lord wald nocht that it wer so;

He maid him for to felye of that fang:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

He for our saik that sufferit to be slane

And lyk a lamb in sacrifice wes dicht

Is like a lyone rissin up agane

And as a gyane raxit him on hicht;

Sprungin is Aurora radius and bricht,

On loft is gone the glorious Appollo,

The blissful day depairtit fro the nycht:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

The grit victour agane is rissin on hicht

That for our querrell to the deth was woundit;

The sone that wox all paill now schynis bricht,

And dirknes clerit, our fayth is now refoundit;

The knell of mercy fra the hevin is soundit,

The Cristin ar deliverit of their wo,

The Jowis and thair errour ar confoundit:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

The fo is chasit, the battell is done ceis,

The presone brokin, the jevellouris fleit and flemit;

The weir is gon, confermit is the peis,

The fetteris lowsit and the dungeoun temit,

The ransoun maid, the presoneris redemit;

The feild is win, ourcumin is the fo,

Dispulit of the tresur that he yemit:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

Done is a battell on the dragon blak;

Our campioun Chryst coufoundit hes his force:

The yettis of hell ar brokin with a crak,

The signe triumphall rasit is of the croce,

The divillis trymmillis with hiddous voce,

The saulis ar borrowit and to the bliss can go,

Chryst with his blud our ransonis dois indoce:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

Dungin is the deidly dragon Lucifer,

The crewall serpent with the mortall stang,

The auld keen tegir with his teith on char

Quhilk in a wait hes lyne for us so lang

Thinking to grip us in his clowis strang:

The merciful lord wald nocht that it wer so;

He maid him for to felye of that fang:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

He for our saik that sufferit to be slane

And lyk a lamb in sacrifice wes dicht

Is like a lyone rissin up agane

And as a gyane raxit him on hicht;

Sprungin is Aurora radius and bricht,

On loft is gone the glorious Appollo,

The blissful day depairtit fro the nycht:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

The grit victour agane is rissin on hicht

That for our querrell to the deth was woundit;

The sone that wox all paill now schynis bricht,

And dirknes clerit, our fayth is now refoundit;

The knell of mercy fra the hevin is soundit,

The Cristin ar deliverit of their wo,

The Jowis and thair errour ar confoundit:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

The fo is chasit, the battell is done ceis,

The presone brokin, the jevellouris fleit and flemit;

The weir is gon, confermit is the peis,

The fetteris lowsit and the dungeoun temit,

The ransoun maid, the presoneris redemit;

The feild is win, ourcumin is the fo,

Dispulit of the tresur that he yemit:

Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro!

Saturday, 23 April 2011

Stond wel, Moder, under rode

BL Royal 6 E VII f.531 (14th century)

"Stond wel, Moder, under rode,

Bihold thi child wyth glade mode;

Blythe, Moder, mittu ben."

"Sune, quu may blithe stonden?

Hi se thin feet, hi se thin honden

Nayled to the harde tre."

"Moder, do wey thi wepinge:

Hi thole this ded for mannes thinge;

For owen gilte tholi non."

"Sune, hi fele the dede stunde;

The swerd is at min herte grunde,

That me byhytte Symeon."

"Moder, reu upon thi bern:

Thu wasse awey tho blodi teren,

It don me werse than mi ded."

"Sune, hu mitti teres wernen?

Hy se tho blodi flodes hernen

Huth of thin herte to min fet."

"Moder, ny y may thee seyn,

Bettere is that ic one deye

Than al mankyn to helle go."

"Sune, y se thi bodi swngen,

Thi brest, thin hond, thi fot thur-stungen

No selli thou me be wo."

"Moder, if y dar thee tellen,

Yif y ne deye, thu gost to helle;

Hi thole this ded for thine sake."

"Sune, thu best me so minde.

With me nout; it is mi kinde

That y for thee sorye make."

"Moder, merci, let me deyen,

For Adam ut of helle beyn

And al mankin that is forloren."

"Sune, wat sal me to rede?

Thi pine pined me to dede;

Let me deyn thee biforen."

"Moder, mitarst thi mith leren

Wat pine tholen that childre beren,

Wat sorwe haven that child forgon."

"Sune, y wot y kan thee tellen,

Bute it be the pine of helle,

More sorwe ne woth y non."

"Moder, reu of moder kare,

Nu thu wost of moder fare,

Thou thu be clene mayden man."

"Sune, help alle at nede,

Alle tho that to me greden —

Mayden, wyf, and fol wyman."

"Moder, y may no lenger duellen;

The time is cumen y fare to helle,

The thridde day y rise upon."

"Sune, y wyle withe funden.

Y deye ywis of thine wnden;

So reuful ded was nevere non."

When he ros than fel thi sorwe:

The blisse sprong the thridde morewe

Wen blithe, Moder, wer thu tho.

Moder, for that ilke blisse

Bisech ure God, ure sinnes lesse,

Thu be hure chel ayen hure fo.

Blisced be thu, quen of hevene,

Bring us ut of helle levene

Thurth thi dere sunes mith.

Moder, for that hithe blode

That he sadde upon the rode

Led us into hevene lith. Amen.

This thirteenth-century poem imagines a dialogue between Mary and Christ as he hangs upon the cross. Meditation on the sorrows of Mary at the foot of the cross, as a way of imaginatively entering into the experience of the Crucifixion, was an increasingly popular devotional theme in this period; you can read other Middle English lyrics on the same subject here, and the most famous example today is probably the 'Stabat Mater Dolorosa', a thirteenth-century Latin hymn written in Italy. The English 'Stond wel, moder', by approaching the scene through dialogue (and only dialogue, until the last two verses), creates a particularly effective impression of immediacy and drama. The interaction between their speeches is vivid and believable: they talk past each other, Christ trying to comfort her and explain the necessity of his death, while his mother is unable to look beyond his immediate suffering. The opening lines ask of her an impossible, paradoxical emotional response: to rejoice as she sees her son dying. Her anguished incredulity - 'how can I be joyful?' - is the reader's entry into this mystery, to see the loving purpose behind this terrible grief.

One of the manuscripts of the poem includes music too, and here it is being sung:

The poem survives in several manuscripts (there's a list here). My translation, preserving some of the beautiful rhymes:

"Stand well, Mother, under the rood,

Behold your child with a glad mood, [mind]

Joyful, Mother, you may be."

"Son, how may I joyful stand?

I see your feet, I see your hands

Nailed to the hard tree."

"Mother, cease your weeping:

I suffer this death for mankind's thing; [sake]

For my guilt I suffer none."

"Son, I feel your death wound;

The sword is at my heart's ground,

As promised to me Simeon."

"Mother, have pity on your bairn, [child]

And wash away those bloody teren, [tears]

They hurt me worse than my death!"

"Son, how may I these tears shun?

I see those bloody floods run

Out of your heart to my feet."

"Mother, now I may you say:

Better that I alone should die

Than all mankind should go to hell."

"Son, I see your body swung,

Your breast, your hand, your foot through-stung; [pierced]

No wonder that I mourn!"

"Mother, if I dare you tell,

If I die not, you will go to hell;

I suffer this death for your sake."

"Son, you are so meek and kind;

Blame me not, it is my kind [nature]

That I for you this sorrow make."

"Mother, have mercy! let me die,

Adam out of hell to buy

And all mankind that is forlorn!"

"Son, what would you have me do?

Your pain pains me to death;

Let me die before you."

"Mother, now you may well learn

What pain they endure who children bear,

What sorrow they have who children lose."

"Son, indeed, I can you tell,

No sorrow but the pain of hell

Is greater than to suffer so!"

"Mother, pity a mother's care,

Now you know how mothers fare,

Though you are a pure virgin."

"Son, help all at need,

All those that to me greede, [cry]

Maiden, wife, and unchaste woman."

"Mother, I may no longer dwell;

The time is come, I go to hell,

The third day I will rise upon."

"Son, I will with you go;

I die, indeed, of your wounds;

Such pitiful death was never none."

When he rose then fell her sorrow:

The bliss sprang up the third morrow.

Joyful, Mother, were you then!

Mother, for that very bliss

Beseech your son, our sins release,

You are our shield against the foe.

Blessed be you, full of bliss,

Let us never heaven miss

Through your dear son's might.

Mother, for that selfsame blood

That he shed upon the rood

Lead us into heaven's light. Amen.

It's interesting to contrast this poem with those which dramatise a conversation between the infant Christ and his mother (this one, for instance), and to see that the specific focus on women here ('Moder, reu of moder kare,/Nu thu wost of moder fare' and Mary's appeal for 'mayden, wyf, and fol wyman') is also echoed by a number of contemporary devotional poems. The most memorable is the brutal 'O all women that ever were born', where Mary compares herself, as she cradles her dead son and traces the wounds on his body, to happy mothers who lovingly dance their children on their laps. It's almost impossibly painful to read, a poignant reminder, in the words of this poem, 'what sorrow they have that children bear". There was a medieval tradition that it was at the Crucifixion that Mary, who suffered no pain in her pregnancy and childbirth, came at last to feel the anguish of motherhood, and so to sympathise with and support all human mothers.

Some of my favourite Middle English poems on the subject of the Passion can be found under this tag. A few more images of Mary at the foot of the cross, from the Anglo-Saxon period to the fourteenth century:

British Library, Harley 2904 f.3v (10th century)

British Library, Arundel 60, f.12v (late 11th century)

BL Arundel 157 f.10v (13th century)

BL Add. 28681, f. 6 (13th century)

BL Egerton 2781 f.157 (14th century)

A St George's Day Carol

St George in 15th-century stained glass (St Winnow, Cornwall)

Enfors we us with all our might

To love Seint George, our Lady knight.

Worship of virtu is the mede,

And seweth him ay of right:

To worship George then have we nede,

Which is our soverein Lady's knight.

He keped the mad from dragon’s dred,

And fraid all France and put to flight.

At Agincourt, the crownecle ye red,

The French him see foremost in fight.

In his virtu he wol us lede

Againis the Fend, the ful wight,

And with his banner us oversprede,

If we him love with all oure might.

St George from Haddon Hall

This fifteenth-century carol to St George comes from BL Egerton 3307. Here's a translation:

Let us do our best, with all our might

To love St George, our Lady's knight.

Honour is the reward of virtue

And always rightly follows it,

So we ought to honour George

Who is our sovereign Lady's knight.

He saved the maiden from the threat of the dragon

And scared the French and put them to flight.

At Agincourt, as we read in the chronicle,

The French saw him foremost in the battle.

With his power he will lead us

Against the devil, that wicked creature,

And spread his banner over us,

If we love him with all our might.

The reference in the second stanza is to the legend that St George had appeared above the battle at Agincourt in 1415 and brought victory to the English. (The manuscript in which this carol appears is dated to between 1430 and 1444, so this is an up-to-date reference.) 'Our Lady's knight' is to be taken quite literally: in medieval tradition St George was closely associated with the Virgin, and one strand of his legend tells how she brought him back from the dead to fight the dragon. This story is illustrated in the following image from a 14th-century Book of Hours (BL Yates Thompson 13, f.154), where the Virgin appears to St George in his tomb and gives him a coat of mail...

...while from the facing page a handy angel brings him a horse and shield:

Friday, 22 April 2011

Christ the Knight

"Crist," seith Seinte Pawel, "luvede swa his leofmon thet he yef for hire the pris of him-seolven." Neometh nu gode yeme, mine leove sustren, for-hwi me ah him to luvien. Earst as a mon the woheth, as a king thet luvede a gentil povre leafdi of feorrene londe. He sende his sonden bivoren - thet weren the patriarches ant te prophetes of the alde testament - with leattres i-sealet. On ende he com him-seolven ant brohte the Godspel as leattres i-openet ant wrat with his ahne blod saluz to his leofmon, luve-gretunge, for-te wohin hire with ant hire luve wealden. Her-to falleth a tale, a wrihe forbisne.

A leafdi wes mid hire fan biset al abuten, hire lond al destruet, ant heo al povre in-with an eorthene castel. A mihti kinges luve wes thah biturnd upon hire swa unimete swithe, thet he for wohlech sende hire his sonden, an efter other, ofte somet monie, sende hire beawbelez bathe feole ant feire, sucurs of liveneth, help of his hehe hird to halden hire castel. Heo underfeng al as on unrecheles, ant swa wes heard i-heortet, thet hire luve ne mahte he neaver beo the neorre.

Hwet wult tu mare? He com him-seolf on ende, schawde hire his feire neb, as the the wes of alle men feherest to bihalden, spec se swithe swoteliche, ant wordes se murie, thet ha mahten deade arearen to live, wrahte feole wundres ant dude muchele meistries bivoren hire eh-sihthe, schawde hire his mihte, talde hire of his kinedom, bead to makien hire cwen of al thet he ahte. Al this ne heold nawt - nes this hoker wunder?

For heo nes neaver wurthe for-te beon his thuften, ah swa thurh his deboneirte luve hefde overcumen him, thet he seide on ende, "Dame, thu art i-weorret ant thine van beoth se stronge thet tu ne maht nanes-weis withute mi sucurs edfleon hare honden, thet ha ne don the to scheome death efter al thi weane. Ich chulle for the luve of the neome thet feht up-o me ant arudde the of ham the thi death secheth. Ich wat thah to sothe thet ich schal bituhen ham neomen deathes wunde, ant ich hit wulle heorteliche for-te ofgan thin heorte. Nu thenne biseche ich the, for the luve thet ich cuthe the, thet tu luvie me lanhure efter the ilke dede dead, hwen thu naldest lives." Thes king dude al thus: arudde hire of alle hire van, ant wes him-seolf to wundre i-tuket ant i-slein on ende - thurh miracle aras thah from deathe to live. Nere theos ilke leafdi of uveles cunnes cunde, yef ha over alle thing ne luvede him her-efter?

Thes king is Jesu, Godes sune, thet al o thisse wise wohede ure sawle, the deoflen hefden biset. Ant he as noble wohere efter monie messagers ant feole god-deden com to pruvien his luve ant schawde thurh cnihtschipe thet he wes luve-wurthe, as weren sum-hwile cnihtes i-wunet to donne - dude him i turneiment ant hefde for his leoves luve his scheld i feht as kene cniht on euche half i-thurlet. His scheld, the wreah his Godd-head, wes his leove licome thet wes i-spread o rode, brad as scheld buven in his i-strahte earmes, nearow bineothen as the an fot - efter mon ies wene - set up-o the other.

From Ancrene Wisse, Part 7. That is:

Christ, says St Paul, so loved his beloved that he gave for her the price of himself. Now pay good attention, my dear sisters, and learn why we should love him. First, as a man who woos, like a king who loved a noble poor lady from a distant land. He sent his messengers ahead with sealed letters - these were the patriarchs and prophets of the Old Testament. In the end he came himself and brought the gospel as opened letters, and wrote with his own blood greetings to his beloved, a salutation of love in order to woo her and gain her love. There is a story about this, an example with a hidden meaning.

A lady was besieged all around with enemies, her land all laid waste, and herself made poor, within a castle made of earth. However, a mighty king loved her so extravagantly that he sent her his messengers in courtship, one after another, often many together; he sent her many fair and splendid gifts, reinforcements and provisions, and help from his noble army to protect her castle. She received all these things without thought, and was so hard-hearted that he was never able to come any closer to her love.

What more do you want? In the end he came himself and showed her his beautiful face, as he who was of all men the fairest to look at. He spoke to her so sweetly with words so pleasant that they might bring the dead back to life, performed many marvels and did works of power before her eyes, showed her his power, told her about his kingdom and offered to make her queen of all that he owned. All this was of no use. Is not such disdain a strange thing? For she was not worthy to be his handmaid. But through his graciousness love had so vanquished him that in the end he said, "Lady, you are beleaguered, and your enemies are so strong that you will not escape their hands by any means without my help; they will put you to a shameful death after all your misery. Because of my love for you, I want to take the battle upon myself and deliver you from those who seek your death. However, I know that among them I shall receive my death-wound, and I will do so with all my heart, to gain your heart. So now I beseech you, for the love which I have made known to you, that you will at least love me after this deed, when I am dead, if you will not when I am alive." The king did all this: he delivered her from all her enemies and was outrageously ill-treated himself, and eventually slain; by a miracle he rose from the dead to life. Was not this lady from the stock of a wicked race, if she did not love him after this above all things?

This king is Jesus, the Son of God, who in this way wooed our souls, which the devil had besieged; and, like a noble suitor, after many messengers and many acts of kindness he came himself to give proof of his love, and showed by his chivalry that he was worthy to be loved, as knights used to do at one time: he fought in a tournament, and for the love of his beloved had a shield in the battle, like a valiant knight, pierced on either side. His shield, which concealed his Godhead, was his precious body that was spread on the cross: broad like a shield at the top across his outstretched arms, and narrow beneath, since one foot, as many people think, was placed over the other.

Good Friday: I sike when I singe

An anonymous late thirteenth-century poem on the Crucifixion.

1. I sike when I singe

For sorewe that I se,

When I with wepinge

Beholde upon the tre

And se Jesu, the swete

His herte blod forlete

For the love of me;

His woundes waxen wete,

They wepend stille and mete;

Mary, reweth thee.

2. Heye upon a downe

Ther all folk it se may

A mile from uch towne

Aboute the midday

The rode is up arered;

His frendes aren afered

And clingeth so the clay;

The rode stond in stone,

Marye stond hire one,

And seith "Weylaway."

3. When I thee beholde

With eyen bright bo

And thy body colde

Thy ble waxeth blo;

Thou hengest all of blode,

So heye upon the rode,

Betwene theves two.

Who may sike more?

Marye wepeth sore

And siht all this wo.

4. The nailes beth too stronge,

The smithes are too sleye

Thou bledest all too longe,

The tre is all too heye;

The stones beth all wete.

Alas! Jesu the swete

For now frend hast thou non

Bote Seint Johan, mourninde,

And Marye, wepinde,

For pine that thee is on.

5. Ofte when I sike

And makie my mon,

Well ille thah me like,

Wonder is it non

When I se honge heye

And bittre pines dreye

Jesu, my lemman,

His wondes sore smerte,

The spere all to his herte

And thourh his sides gon.

6. Ofte when I sike

With care I am thourhsoght;

When I wake, I wike,

Of sorewe is all my thoght.

Alas! Men beth wode

That swereth by the rode,

And selleth him for noght

That boghte us out of sinne.

He bring us to winne,

That hath us dere boght!

Translation:

1. I sigh when I sing

For the sorrow I see

When I with weeping

Gaze upon the tree

And see Jesus, the sweet,

His heart's blood lost

For love of me;

His wounds grow wet

They weep copiously;

Mary, it grieves thee!

2. High upon a hill

Where everyone may see

A mile from any town

At midday,

The Rood is raised up.

His friends are afraid,

Cast down by sorrow

The Rood stands on the stone,

Mary stands alone,

And cries, "Weylaway!" ["Alas!"]

3. When I behold thee,

Thy two eyes bright

And thy body cold

And thy face like ash,

Hanging, covered in blood,

So high upon the Rood

Between the two thieves -

Who can sorrow more?

Mary weeps sore,

Seeing all this woe.

4. The nails are too strong,

The smiths are too cunning,

Thy bleeding is too long,

The tree is too high;

The stones are all wet;

Alas, Jesus, the sweet!

For now thou hast no friend

Except St John, mourning,

And Mary, weeping,

Because of thy pain.

5. Often when I sigh

And make my complaint

It is great distress to me,

And it is no wonder -

When I see, hanging high,

Suffering bitter pains,

Jesus, my darling;

His wounds smart sore,

The spear goes to his heart,

And through his sides.

6. Often when I sigh,

I am pierced through with grief;

When I wake I grow weak,

All my thoughts are of sorrow.

Alas, men are mad

Who swear by the cross

And count him as nothing

Who saved us from sin! [literally: 'sell him for nothing who bought us']

May he bring us into joy

Who has bought us at such a price!

1. I sike when I singe

For sorewe that I se,

When I with wepinge

Beholde upon the tre

And se Jesu, the swete

His herte blod forlete

For the love of me;

His woundes waxen wete,

They wepend stille and mete;

Mary, reweth thee.

2. Heye upon a downe

Ther all folk it se may

A mile from uch towne

Aboute the midday

The rode is up arered;

His frendes aren afered

And clingeth so the clay;

The rode stond in stone,

Marye stond hire one,

And seith "Weylaway."

3. When I thee beholde

With eyen bright bo

And thy body colde

Thy ble waxeth blo;

Thou hengest all of blode,

So heye upon the rode,

Betwene theves two.

Who may sike more?

Marye wepeth sore

And siht all this wo.

4. The nailes beth too stronge,

The smithes are too sleye

Thou bledest all too longe,

The tre is all too heye;

The stones beth all wete.

Alas! Jesu the swete

For now frend hast thou non

Bote Seint Johan, mourninde,

And Marye, wepinde,

For pine that thee is on.

5. Ofte when I sike

And makie my mon,

Well ille thah me like,

Wonder is it non

When I se honge heye

And bittre pines dreye

Jesu, my lemman,

His wondes sore smerte,

The spere all to his herte

And thourh his sides gon.

6. Ofte when I sike

With care I am thourhsoght;

When I wake, I wike,

Of sorewe is all my thoght.

Alas! Men beth wode

That swereth by the rode,

And selleth him for noght

That boghte us out of sinne.

He bring us to winne,

That hath us dere boght!

Translation:

1. I sigh when I sing

For the sorrow I see

When I with weeping

Gaze upon the tree

And see Jesus, the sweet,

His heart's blood lost

For love of me;

His wounds grow wet

They weep copiously;

Mary, it grieves thee!

2. High upon a hill

Where everyone may see

A mile from any town

At midday,

The Rood is raised up.

His friends are afraid,

Cast down by sorrow

The Rood stands on the stone,

Mary stands alone,

And cries, "Weylaway!" ["Alas!"]

3. When I behold thee,

Thy two eyes bright

And thy body cold

And thy face like ash,

Hanging, covered in blood,

So high upon the Rood

Between the two thieves -

Who can sorrow more?

Mary weeps sore,

Seeing all this woe.

4. The nails are too strong,

The smiths are too cunning,

Thy bleeding is too long,

The tree is too high;

The stones are all wet;

Alas, Jesus, the sweet!

For now thou hast no friend

Except St John, mourning,

And Mary, weeping,

Because of thy pain.

5. Often when I sigh

And make my complaint

It is great distress to me,

And it is no wonder -

When I see, hanging high,

Suffering bitter pains,

Jesus, my darling;

His wounds smart sore,

The spear goes to his heart,

And through his sides.

6. Often when I sigh,

I am pierced through with grief;

When I wake I grow weak,

All my thoughts are of sorrow.

Alas, men are mad

Who swear by the cross

And count him as nothing

Who saved us from sin! [literally: 'sell him for nothing who bought us']

May he bring us into joy

Who has bought us at such a price!

Thursday, 21 April 2011

St Anselm, Anglo-Saxonist

St Anselm of Canterbury, one of the greatest medieval theologians, is commemorated today, on the anniversary of his death in 1109. I don't have much to say about him today, but I want to give him credit for being one of the first people (perhaps the first person) after the Norman Conquest to give due honour to St Ælfheah, about whom I wrote the other day. Lanfranc, the first post-Conquest Archbishop of Canterbury, respected his predecessor Ælfheah as a good man and archbishop, but was not convinced he was actually a saint. In fact, Lanfranc wasn't entirely convinced of the sanctity of any the barbarically-named priests and princes whom the Anglo-Saxons had venerated as saints. It probably wasn't anti-English prejudice, though it has been interpreted that way; Lanfranc approached the question like the scholar he was - he wanted proof, or at least a reasonable argument. He stripped Canterbury's calendar of all its pre-Conquest saints, but consulted Anselm (then on his first visit to Canterbury in 1079) about the question of whether Ælfheah was really a martyr, since it was not clear whether he had strictly died in defence of the Christian faith.

You might think that dying by having ox-bones thrown at you by pagan Vikings would be a good qualification - but not in Lanfranc's eyes! The issue was that Ælfheah had been killed for refusing to pay a ransom to his captors, and not necessarily because he was a Christian. So Anselm reasoned that Ælfheah had died because he refused to use other people's money to buy his own freedom - which would be a sin against justice. To refuse to sin against justice was to refuse to sin against God, he said, and so Ælfheah was a martyr for truth, just as John the Baptist was, and therefore a martyr for God. "There is the witness of Holy Scripture, as you, Father, very well know," Anselm said to Lanfranc, "that Christ is both truth and justice; so he who dies for truth and justice dies for Christ. But he who dies for Christ is, as the Church holds, a martyr. Now St Alphege as truly suffered for justice as St John did for truth. So why should anyone have more doubt about the true and holy martyrdom of the one than of the other?" This argument convinced Lanfranc and delighted the Canterbury monks, and occasioned the writing of a wonderful Life of Alphege.

When Anselm later succeeded Lanfranc as Archbishop of Canterbury, he supposedly consulted Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester, "sole survivor of the old Fathers of the English people", to ask him about the customs of the English church which had been so violently eradicated. This story (plus the one about Henry I and Matilda) contributes substantially to making Anselm one of my favourite medieval people. Good man!

You might think that dying by having ox-bones thrown at you by pagan Vikings would be a good qualification - but not in Lanfranc's eyes! The issue was that Ælfheah had been killed for refusing to pay a ransom to his captors, and not necessarily because he was a Christian. So Anselm reasoned that Ælfheah had died because he refused to use other people's money to buy his own freedom - which would be a sin against justice. To refuse to sin against justice was to refuse to sin against God, he said, and so Ælfheah was a martyr for truth, just as John the Baptist was, and therefore a martyr for God. "There is the witness of Holy Scripture, as you, Father, very well know," Anselm said to Lanfranc, "that Christ is both truth and justice; so he who dies for truth and justice dies for Christ. But he who dies for Christ is, as the Church holds, a martyr. Now St Alphege as truly suffered for justice as St John did for truth. So why should anyone have more doubt about the true and holy martyrdom of the one than of the other?" This argument convinced Lanfranc and delighted the Canterbury monks, and occasioned the writing of a wonderful Life of Alphege.

When Anselm later succeeded Lanfranc as Archbishop of Canterbury, he supposedly consulted Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester, "sole survivor of the old Fathers of the English people", to ask him about the customs of the English church which had been so violently eradicated. This story (plus the one about Henry I and Matilda) contributes substantially to making Anselm one of my favourite medieval people. Good man!

Wednesday, 20 April 2011

Another April Poem: Cotswold Love

Before Holy Week proper takes over, here's another cheerful poem about spring, by John Drinkwater (1882-1937). All the places named are in Gloucestershire, but Oxfordshire is part of the Cotswolds too, so it's almost a local poem...

Cotswold Love

Blue skies are over Cotswold

And April snows go by,

The lasses turn their ribbons

For April's in the sky,

And April is the season

When Sabbath girls are dressed,

From Rodboro' to Campden,

In all their silken best.

An ankle is a marvel

When first the buds are brown,

And not a lass but knows it

From Stow to Gloucester town.

And not a girl goes walking

Along the Cotswold lanes

But knows men's eyes in April

Are quicker than their brains.

It's little that it matters,

So long as you're alive,

If you're eighteen in April,

Or rising sixty-five,

When April comes to Amberley

With skies of April blue,

And Cotswold girls are briding

With slyly tilted shoe.

Cotswold Love

Blue skies are over Cotswold

And April snows go by,

The lasses turn their ribbons

For April's in the sky,

And April is the season

When Sabbath girls are dressed,

From Rodboro' to Campden,

In all their silken best.

An ankle is a marvel

When first the buds are brown,

And not a lass but knows it

From Stow to Gloucester town.

And not a girl goes walking

Along the Cotswold lanes

But knows men's eyes in April

Are quicker than their brains.

It's little that it matters,

So long as you're alive,

If you're eighteen in April,

Or rising sixty-five,

When April comes to Amberley

With skies of April blue,

And Cotswold girls are briding

With slyly tilted shoe.

Tuesday, 19 April 2011

The Story of Archbishop Alphege

On 19th April in 1012, the Archbishop of Canterbury was murdered by a Viking army. Archbishop Ælfheah (whose name is often modernised to Alphege) was captured when the Vikings besieged the city of Canterbury in September 1011, and kept prisoner with the Danish fleet in Greenwich until the following Easter. He refused to allow ransom to be paid for him; England had been paying Danegeld to the Viking army since 991, with little result. Angry at this refusal, the drunken army pelted him with bones and ox-heads, until one of them struck him on the head with an axe, and he was killed (a later chronicler said this was a mercy blow, from a Danish man named Thrum, whom the Archbishop had converted to Christianity during his captivity).

Naturally enough the Archbishop was considered by the English to be a martyr, and venerated as a saint. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral, and in 1023, after the Danes' final victory, King Cnut had his relics removed to Canterbury, as an act of reparation.

I'm in an Old English mood today, so here's the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's account of these years, with my translation. The destruction of Canterbury provoked the usually dispassionate chronicler to anguished lament:

1011

Þa on ðissum geare betweox Natiuitas Sancte Marie 7 Sancte Michaeles mæssan hi ymbsæton Cantwareburuh, 7 hi into comon þuruh syruwrencas, forðan Ælmær hi becyrde, þe se arcebisceop Ælfeah ær generede æt his life. 7 hi þær ða genaman þone arcebisceop Ælfeah 7 Ælfweard cynges gerefan 7 Leofrune abbatissan 7 Godwine bisceop, 7 Ælfmær abbod hi leton aweg. 7 hi ðær genamon inne ealle þa gehadodan men 7 weras 7 wif, þæt wæs unasecgendlic ænigum men hu micel þæs folces wæs, 7 on þære byrig syþþan wæron swa lange swa hi woldon. 7 hi ða hæfdon þa buruh ealle asmeade, wendon him þa to scypan 7 læddon þone arcebisceop mid him. Wæs ða ræpling, se ðe ær wæs heafod Angelkynnes 7 Cristendomes. Þær man mihte ða geseon yrmðe þær man oft ær geseah blisse on þære earman byrig þanon com ærest Cristendom 7 blis for Gode 7 for worulde. 7 hi hæfdon þone arcebisceop mid him swa lange oð þæne timan þe hi hine gemartiredon.

In this year, between the Nativity of St Mary [8 September] and Michaelmas [29 September], they besieged Canterbury. They got in through trickery, because Ælmær, whose life Archbishop Ælfheah had once saved, delivered the city to them. And there they captured Archbishop Ælfheah and Ælfweard the king’s reeve, and Abbess Leofrune and Bishop Godwine, but they let Abbot Ælfmær go free. They captured all ordained people, both men and women – it was impossible for anyone to say how many people that was – and they stayed in the city afterwards as long as they chose. And when they had been through the whole city, they went to the ships and took the archbishop with them. Then was he a captive, who had been the head of the English race and of Christendom! There wretchedness might be seen where bliss had often been seen before, in that poor city from where there first came to us Christianity and joy before God and before the world. They kept the archbishop with them for a long time, until they martyred him.

1012

Ða on þæne Sæternesdæg wearð þa se here swyðe astyred angean þone bisceop, forþam ðe he nolde him nan feoh behaten, ac he forbead þæt man nan þing wið him syllan ne moste. Wæron hi eac swyþe druncene, forðam þær wæs broht win suðan. Genamon þa ðone bisceop, læddon hine to hiora hustinge on ðone Sunnanæfen octabas Pasce , þa wæs .xiii. Kalendas Maius , 7 hine þær ða bysmorlice acwylmdon, oftorfedon mid banum 7 mid hryþera heafdum, 7 sloh hine ða an hiora mid anre æxe yre on þæt heafod, þæt mid þam dynte he nyþer asah, 7 his halige blod on þa eorðan feol, 7 his haligan sawle to Godes rice asende. 7 mon þone lichaman on mergen ferode to Lundene, 7 þa bisceopas Eadnoþ 7 Ælfun 7 seo buruhwaru hine underfengon mid ealre arwurðnysse 7 hine bebyrigdon on Sancte Paules mynstre, 7 þær nu God sutelað þæs halgan martires mihta.

On the Saturday [after Easter] the army grew very angry with the bishop because he would not promise them any money, and he forbade that anyone should pay any money for his ransom. They were very drunk, because they had wine from the south. They took the bishop and led him to their husting [their assembly] on the evening of the Sunday after Easter, the thirteenth before the calends of May. And there they shamefully killed him, pelting him with bones and with the heads of oxen, and one of them struck him on the back of the head with an iron axe. With that blow he sank to the ground, and his holy blood fell on the ground, and his holy soul rose to the kingdom of God. In the morning his body was carried to London, and the bishops Eadnoth and Ælfun and the citizens received him with great honour, and they buried him at St Paul's minster, and there God now shows the virtues of the holy martyr with miracles.

Naturally enough the Archbishop was considered by the English to be a martyr, and venerated as a saint. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral, and in 1023, after the Danes' final victory, King Cnut had his relics removed to Canterbury, as an act of reparation.

I'm in an Old English mood today, so here's the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's account of these years, with my translation. The destruction of Canterbury provoked the usually dispassionate chronicler to anguished lament:

1011

Þa on ðissum geare betweox Natiuitas Sancte Marie 7 Sancte Michaeles mæssan hi ymbsæton Cantwareburuh, 7 hi into comon þuruh syruwrencas, forðan Ælmær hi becyrde, þe se arcebisceop Ælfeah ær generede æt his life. 7 hi þær ða genaman þone arcebisceop Ælfeah 7 Ælfweard cynges gerefan 7 Leofrune abbatissan 7 Godwine bisceop, 7 Ælfmær abbod hi leton aweg. 7 hi ðær genamon inne ealle þa gehadodan men 7 weras 7 wif, þæt wæs unasecgendlic ænigum men hu micel þæs folces wæs, 7 on þære byrig syþþan wæron swa lange swa hi woldon. 7 hi ða hæfdon þa buruh ealle asmeade, wendon him þa to scypan 7 læddon þone arcebisceop mid him. Wæs ða ræpling, se ðe ær wæs heafod Angelkynnes 7 Cristendomes. Þær man mihte ða geseon yrmðe þær man oft ær geseah blisse on þære earman byrig þanon com ærest Cristendom 7 blis for Gode 7 for worulde. 7 hi hæfdon þone arcebisceop mid him swa lange oð þæne timan þe hi hine gemartiredon.

In this year, between the Nativity of St Mary [8 September] and Michaelmas [29 September], they besieged Canterbury. They got in through trickery, because Ælmær, whose life Archbishop Ælfheah had once saved, delivered the city to them. And there they captured Archbishop Ælfheah and Ælfweard the king’s reeve, and Abbess Leofrune and Bishop Godwine, but they let Abbot Ælfmær go free. They captured all ordained people, both men and women – it was impossible for anyone to say how many people that was – and they stayed in the city afterwards as long as they chose. And when they had been through the whole city, they went to the ships and took the archbishop with them. Then was he a captive, who had been the head of the English race and of Christendom! There wretchedness might be seen where bliss had often been seen before, in that poor city from where there first came to us Christianity and joy before God and before the world. They kept the archbishop with them for a long time, until they martyred him.

1012

Ða on þæne Sæternesdæg wearð þa se here swyðe astyred angean þone bisceop, forþam ðe he nolde him nan feoh behaten, ac he forbead þæt man nan þing wið him syllan ne moste. Wæron hi eac swyþe druncene, forðam þær wæs broht win suðan. Genamon þa ðone bisceop, læddon hine to hiora hustinge on ðone Sunnanæfen octabas Pasce , þa wæs .xiii. Kalendas Maius , 7 hine þær ða bysmorlice acwylmdon, oftorfedon mid banum 7 mid hryþera heafdum, 7 sloh hine ða an hiora mid anre æxe yre on þæt heafod, þæt mid þam dynte he nyþer asah, 7 his halige blod on þa eorðan feol, 7 his haligan sawle to Godes rice asende. 7 mon þone lichaman on mergen ferode to Lundene, 7 þa bisceopas Eadnoþ 7 Ælfun 7 seo buruhwaru hine underfengon mid ealre arwurðnysse 7 hine bebyrigdon on Sancte Paules mynstre, 7 þær nu God sutelað þæs halgan martires mihta.

On the Saturday [after Easter] the army grew very angry with the bishop because he would not promise them any money, and he forbade that anyone should pay any money for his ransom. They were very drunk, because they had wine from the south. They took the bishop and led him to their husting [their assembly] on the evening of the Sunday after Easter, the thirteenth before the calends of May. And there they shamefully killed him, pelting him with bones and with the heads of oxen, and one of them struck him on the back of the head with an iron axe. With that blow he sank to the ground, and his holy blood fell on the ground, and his holy soul rose to the kingdom of God. In the morning his body was carried to London, and the bishops Eadnoth and Ælfun and the citizens received him with great honour, and they buried him at St Paul's minster, and there God now shows the virtues of the holy martyr with miracles.

Monday, 18 April 2011

An April Poem: The West Wind

by John Masefield (1878-1967), Poet Laureate and West Country boy. It's best read aloud.

The West Wind

It's a warm wind, the west wind, full of birds' cries;

I never hear the west wind but tears are in my eyes.

For it comes from the west lands, the old brown hills.

And April's in the west wind, and daffodils.

It's a fine land, the west land, for hearts as tired as mine,

Apple orchards blossom there, and the air's like wine.

There is cool green grass there, where men may lie at rest,

And the thrushes are in song there, fluting from the nest.

"Will ye not come home brother? ye have been long away,

It's April, and blossom time, and white is the may;

And bright is the sun brother, and warm is the rain -

Will ye not come home, brother, home to us again?

"The young corn is green, brother, where the rabbits run.

It's blue sky, and white clouds, and warm rain and sun.

It's song to a man's soul, brother, fire to a man's brain,

To hear the wild bees and see the merry spring again.

"Larks are singing in the west, brother, above the green wheat,

So will ye not come home, brother, and rest your tired feet?

I've a balm for bruised hearts, brother, sleep for aching eyes,"

Says the warm wind, the west wind, full of birds' cries.

It's the white road westwards is the road I must tread

To the green grass, the cool grass, and rest for heart and head,

To the violets, and the warm hearts, and the thrushes' song,

In the fine land, the west land, the land where I belong.

Sunday, 17 April 2011

Gloria, laus et honor: Wele, herying and worshipe

Wele, herying and worshipe be to Christ that dere ous boughte,

To wham gradden 'Osanna' children clene of thoughte.

Thou art king of Israel and of Davides kunne,

Blessed king that comest till ous withoute wem of sunne.

All that is in hevene thee herieth under on,

And all thine owne hondewerk and euch dedlich mon.

The folk of Giwes with bowes comen ayeinest thee,

And we with bedes and with song meketh ous to thee.

He kepten thee with worshiping, ayeinst thou shuldest deye,

And we singen to thy worshipe, in trone that sittest heye.

Here wil and here mekinge thou nome tho to thonk;

Queme thee thenne, milsful King, oure offrings of this song.

This is a translation of the Palm Sunday hymn 'Gloria, laus et honor' by the Franciscan friar William Herebert (c.1270-1333). Here's a modernised version:

Glory, praise and honour be to Christ who dear us bought,

To whom cried 'Hosanna' children pure of thought.

You are the king of Israel and of David's kin,

Blessed King who comes to us without the stain of sin.

All that is in heaven praises you as one,

And all your own handiwork and every mortal man.

The Jewish people with boughs came to meet you,

And we with prayers and with songs humble ourselves to you.

They attended you with honour, at the time when you should die,

And we sing to your honour, who in throne sits on high.

Their will and their humility you accepted graciously then;

So may please you, merciful King, our offering of this song.

As always, Herebert produces a creative translation, a fluid and confident reworking of the Latin hymn into an English idiom. The first verse plays effectively on the similarity between the English words king and kin, and the two lines of each verse are neatly linked to each other by alliteration as well as by rhyme: king/kunne/comest, hevene/herieth/hondewerk, bowes/bedes, etc. Since several of the verses are carefully structured as parallels - the first line describes what the people of Jerusalem did, the second what 'we' do on Palm Sunday - linking them through alliteration works to re-enforce the parallels between, for instance, their bowes and our bedes.

Here's the original, by Theodulph of Orleans (d.821):

R: Gloria, laus et honor

tibi sit, Rex Christe, Redemptor:

Cui puerile decus prompsit

Hosanna pium.

1. Israel es tu Rex, Davidis et

inclyta proles:

Nomine qui in Domini,

Rex benedicte, venis.

2. Coetus in excelsis te laudat

caelicus omnis,

Et mortalis homo, et cuncta

creata simul.

3. Plebs Hebraea tibi cum palmis

obvia venit:

Cum prece, voto, hymnis,

adsumus ecce tibi.

4. Hi tibi passuro solvebant