This striking monument stands in a central position in Winchester Cathedral, behind the high altar, and surrounded by empty space. It commemorates the medieval shrine of St Swithun, which was destroyed at the Reformation, and the inscription reads (in Latin on the floor, in English on the monument itself):

Whatever partakes of God is safe in God. All that could perish of Saint Swithun, being enshrined within this place and throughout many ages hallowed by the veneration and honoured by the gifts of faithful pilgrims from many lands, was by a later age destroyed. None could destroy his glory.

The monument itself evokes an absence: beneath the cloth hanging are bare ribs of metal, as of a skeleton stripped of its flesh. Swithun was a very popular saint in medieval England, and his shrine, moved at various times as the cathedral was rebuilt and reordered, was the destination of many pilgrims' journeys. At three o'clock in the morning of 21 September 1538, his shrine was demolished by the Commissioners of Henry VIII, who recorded their intention to 'sweep away all the rotten bones' they found within - bones which had for more than five hundred years been venerated as treasures.

Ælfric tells us that the Anglo-Saxon minster at Winchester, which housed the original shrine of St Swithun, 'was hung all round with the crutches and stools of cripples who had been healed there, from one end to the other on either wall - and even so they could not put half of them up'. No such offerings can be found in Winchester today, but modern pilgrims leave tokens of their presence nonetheless: votive candles, whose flames glow in the reflection of the shrine.

This is the season of All Saints, Hallowtide, and it seems a fitting time to post a collection of pictures on a theme I've been interested in for a while: how English cathedrals and major churches today choose to represent their pre-Reformation history, and especially the history of the medieval saints whose shrines they once housed. In the Middle Ages, these shrines were integral to the life, history, and physical shape of these cathedrals, a tangible embodiment (in every sense) of their shared spiritual life and their collective identity as a community. As at Winchester, these shrines were usually in a prominent and central position in the church, close to the high altar, and the history of most cathedrals was inextricably bound up with the saints whose relics they preserved, who might be their founders, early leaders, or the nucleus around which the community originally grew. The saint was both literally and metaphorically at the heart of the cathedral, and to remove them created a huge gap. When these shrines were destroyed, it left an absence in more ways than the loss of the saint's holy 'rotten bones'.

A number of churches today choose to acknowledge and commemorate that absence, and I'm interested in the different ways they find to do that. This post is a brief journey through the shrines of some of England's medieval saints - or rather, the empty spaces which those shrines once occupied.

Some of these churches are among the oldest surviving institutions in England, with more than a thousand years of tumultuous, yet essentially unbroken continuity, and their saints and their medieval history of pilgrimage are an unavoidable part of their story - unless they are prepared to ignore the first six or seven centuries of their history, and often their own foundation-story, these churches have to find some way of telling that story to visitors. But they don't have to do it with such eloquent generosity to the medieval past as that monument at Winchester does, and the choices they make are interesting. If space is given over to an absence, in the middle of a busy and crowded church, it becomes significant how that space is identified and used. My aim in this post is to illustrate some of the varied ways in which different churches choose to mark out that empty space - with a replica shrine, a plaque, or simply an area left clear - as well as how they encourage their visitors to approach and interact with it. Do they treat it primarily as an architectural feature, as a historical curiosity, or as a place for prayer? It's surprising, perhaps, how often the third of those options is the case; these churches are, of course, all Anglican cathedrals, which makes it all the more remarkable that they (and their visitors and worshippers) are prepared to embrace these relics of medieval Catholic devotion. They don't always call them 'shrines' - is something like that monument to Swithun a shrine itself, or a memorial to a lost shrine? - but it seems a fine line to me between commemorating the shrine and effectively recreating it.

What is clear in all cases, though, is that these saints still matter to the churches which once housed their shrines. They are still a part of the stories these places tell about their own history and identity - not in the ways they would have been in the Middle Ages, but nonetheless in ways which are meaningful and significant both to the churches and to those who visit them. One thing which surprised me at many of these shrines, again and again, was how many votive candles had been left burning beside them by visitors who had been there before me. As a medievalist, I get to hear a great deal about how weird and alien medieval devotion to saints and shrines is to a 'modern audience', but these churches and their visitors seem to feel differently - and that might be worth bearing in mind next time you hear someone holding forth about medieval 'superstition'. Even if they do not subscribe to medieval (or modern) Catholic beliefs about saints and their relics, many of these churches are generous enough to acknowledge that there is something special about a place which was the destination of so many pilgrims' journeys, as if once the shrine itself is gone the thousands of prayers can hallow even the empty air.

Her ongynð secgean be þam Godes sanctam þe on engla lande ærest reston. ('Here begins the account of God's saints who rest in England.')

As I was compiling this post it reminded me of the Anglo-Saxon text known as the 'List of Saints' Resting Places', the opening of which you can see above in an eleventh-century manuscript. This text gives a survey of the saints of England and the places where their relics lie, and many of those saints are those still commemorated in the same places, a thousand years later. This text arranges its saints by rough geographical area - from Northumbria into Mercia, down to East Anglia, Kent and Wessex - so I've mostly followed that order in this post. My collection is far from comprehensive, since it's just really based on places I've visited myself, so there are doubtless many places not included which ought to be - I haven't been to Hereford Cathedral, for instance, which appears to have a magnificently colourful shrine, or to St Albans. St Alban is actually the first saint in the 'List of Saints' Resting Places', followed by Columba - and then comes St Cuthbert, so let's start with him. At Durham Cathedral, the site of Cuthbert's shrine is marked out very prominently:

(image from here)

Visitors are guided to walk around the shrine (up one set of stairs and down another) and reminded that this is a special place, slightly set apart. When I visited last year, a number of people were sitting quietly there or lighting candles. Similarly, in the cathedral's unusual Galilee Chapel at the west end of the church, Bede's tomb is treated as a place for private prayer:

After Cuthbert the 'List of Saints' Resting Places' tells us about its next great Northumbrian saint: Þonne resteð Sancte Oswald cyninge on bebban byrig wið þa sæ, 7 his heafod resteð mid Sancte Cuðberhte 7 his swyðra earm is nu on bebban byrig ('St Oswald the king rests at Bamburgh beside the sea, and his head rests with St Cuthbert, and his right arm is now at Bamburgh'). St Oswald, who died in 642, was a very popular saint, and in the Middle Ages his relics were dispersed between a number of churches: his head was buried with St Cuthbert, and other relics could be found in Gloucester, Peterborough, and at Bamburgh 'beside the sea'.

Within the walls of Bamburgh Castle today, you can visit the chapel where those relics once were:

There's no shrine here or anything like it, but this kind of collection wouldn't be complete without some ruins of medieval churches and chapels; they were shrines too, and the lack of any religious presence here - this is just a space inside a castle - is as much worth noting as its survival elsewhere. Nearby, in the church of St Aidan at Bamburgh, it's slightly different; there you can see a spot associated with St Aidan:

According to Bede, it was St Aidan who - seeing Oswald distributing food to the poor - blessed the king's right hand, exclaiming 'May this hand never wither!' Oswald's right arm, severed at his death in battle, remained miraculously incorrupt, and was later preserved as a relic at Peterborough Abbey. (More of that in a moment...)

Moving further south, down to Lindsey, Lincoln Cathedral has an interesting combination of the medieval and the modern. Lincoln was not a cathedral in the Anglo-Saxon period, so its chief saints are from slightly later: the twelfth-century bishop St Hugh is now the most famous, and part of his medieval shrine survives (on the left of this picture, at the east end of the cathedral). Next to the shrine, the cathedral reserves an area for prayer which houses not just votive candles but some unusual modern candle-holders, known as the 'Gilbert Pots' in honour of St Gilbert of Sempringham - twelfth-century founder of the Gilbertines, Lincolnshire's very own religious order.

Now for Mercia, and the example which first got me interested in the idea for this post: Lichfield Cathedral, which places its Anglo-Saxon saint front and centre.

Lichfield's saint is Chad, who established a monastery and episcopal see here in the middle of the seventh century. St Chad died at Lichfield in 672, and his shrine continued to attract pilgrims throughout the Middle Ages. The site of his shrine was beyond the high altar, and a place is now marked out near the spot with an icon, a plaque, flowers, prayers, and candles:

The sign on the left is information about the shrine of St Chad, on the right a prayer for recent victims of terrorist attacks in London - a striking juxtaposition of the medieval and modern.

Chad's head was kept separately in an upper chapel, which you can also visit:

Modern cathedral visitors like going up and down stairs as much as medieval pilgrims did - crypts and upper chapels feature several times in this collection, as spaces set apart (then and now) as special and self-contained areas for prayer.

Lichfield has some particular advantages in presenting its medieval past to visitors. This is the wonderful 'Lichfield Angel', discovered under the floor of the cathedral in 2003, which may have formed part of the Anglo-Saxon shrine of St Chad. It probably dates to around 800, and is now displayed next to the St Chad Gospels, a beautifully decorated Anglo-Saxon manuscript which has been at Lichfield since at least the eleventh century.

These are two remarkable treasures for a cathedral to have, and they are displayed in an accessible and informative way which puts Chad and his shrine in their historical context. Visiting this summer, I was interested to see how Chad has become integrated into the recent growth of interest in Anglo-Saxon Mercia, sparked partly by the discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009. Lichfield Cathedral is now part of the Mercian Trail, which also incorporates the museums displaying the hoard and Tamworth Castle, all of which provide vivid glimpses into the early history of Mercia. Tourism and pilgrimage have always gone hand-in-hand, and clearly Chad's shrine is now part of a new focus for the heritage industry in this area - it's a fascinating example of how a discovery like the Staffordshire Hoard can provide an impetus for re-imagining how an unfamiliar period of history can be presented to the public. But the prayers and candles at Chad's shrine show this is not 'just' heritage - the visitor is encouraged to reflect on something more.

From this plethora of Anglo-Saxon history, it's an interesting contrast to turn to another Mercian shrine - a much smaller one (and not in a cathedral), but worth mentioning nonetheless because it's such a special place. Repton, which I wrote about at greater length here, has an Anglo-Saxon crypt which may at one time have housed the shrine of St Wigstan. (Þonne resteð Sancte Wigstan on þam mynstre Hreopedune, neah þære ea Treante, says the 'List of Saints' Resting Places'.)

This small, atmospheric space is left dark and unadorned, and here the candles suggest a shrine, without quite attempting to reconstruct one. They are a reminder that this little crypt is not just an amazing architectural survival, but a holy space - in some ways, the closest one can come to visiting the semi-underground kind of arrangement which we know some early medieval shrines had.

Now, like St Guthlac, let's go from Repton to Crowland, where we find a different kind of absence. Crowland was one of the great Fenland abbeys, and the north aisle of what was the abbey church is still in use as the parish church. But the rest of the abbey church is in ruins:

The shrine of St Guthlac would have been around this area, near the high altar, but there's nothing to say where:

In this case the ruin itself serves as the empty space; a church with a ruin attached is a powerful image of destruction. Crowland provides information on Guthlac, but doesn't attempt to recreate his shrine, and in this it's quite a contrast to some of the other great Fenland churches, especially Ely Cathedral, home of the cult of St Etheldreda since the seventh century. At Ely, a prominent and central space is set aside within the choir to commemorate Etheldreda's shrine:

Visitors are also encouraged to light candles before a statue of the saint:

And to take away prayer cards, which describe medieval pilgrimage in sympathetic terms which deftly connect the modern visitor with those who have visited Etheldreda's shrine over the centuries:

This is, as you may have guessed, my own preferred attitude to medieval pilgrimage - to recognise the humanity of those who sought out these shrines, and to treat them not as ignorant superstitious dupes but as people with explicable needs and desires, different from our own, but not beyond our comprehension.

It's funny to see a very different attitude to Ely's in the neighbouring diocese of Peterborough, which adopts a much more negative tone from its fellow cathedrals in talking about medieval saints. When I visited in 2015, this display board in the nave made its opinion clear:

In reference to the arm of St Oswald, kept as a relic at Peterborough before the Reformation, we are told:

Ouch! (How I hate that snotty use of 'curious', which so often comes from people who are resolutely incurious about customs they are determined not to understand...) It probably won't surprise you to learn that I'm inclined to think this attitude - more the tone than the content - is both over-simplified and quite disrespectful to the people who built this great cathedral, but I'm actually surprised it isn't more widely represented in what are, after all, Anglican churches. It is also, however, deeply ironic, because just a few feet away from this condemnation of saints and shrines is... an impromptu shrine.

This is the tomb of Katherine of Aragon, and here people leave pomegranates as offerings (?) to the queen. She's not a saint, but people do love a mistreated princess. Is this more or less 'superstitious' than venerating the relics of St Oswald? Squash out and sneer at relic-veneration all you like, people will just make themselves new saints and new rituals.

But if relics are a step too far, Peterborough does actually have what may be the remains of an Anglo-Saxon shrine:

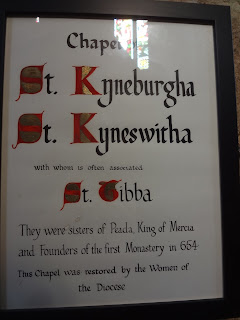

And the saints aren't ignored - there's a chapel dedicated to two of Peterborough's very early female saints (who feature in the 'List of Saints' Resting Places'):

And this nice window to some illustrious Anglo-Saxon Benedictines:

That's St Dunstan, St Æthelwold, King Edgar and Queen Ælfthryth (I think), who were all credited with involvement in the tenth-century refoundation of Peterborough Abbey - and even, in the bottom left, the twelfth-century Peterborough chronicler Hugh Candidus. So it's a good show for the medieval saints, and we'll have to forgive the appearance of that awful word 'superstitious'...

Ely and Peterborough are both beautiful and impressive cathedrals, and to turn from there to Bury St Edmunds - their equal and rival in the Middle Ages - is to realise how easily those beauties could have been lost. Bury St Edmunds no longer has the shrine of St Edmund, which would have stood among what are now the ruins of one of the greatest churches in England:

But in the small church nearby - which is now the cathedral, though much smaller than the abbey church would have been - there's a reminder of the medieval splendour of Edmund's shrine:

This is a tapestry based on an image from the fifteenth-century manuscript BL Harley 2278, a lavishly illustrated manuscript of Lydgate's Life of St Edmund. It shows Henry VI praying at Edmund's golden shrine - a reminder of what once stood where the grass now grows.

It's worth mentioning, of course, that the story of these shrines is not all one of destruction - sometimes the twenty-first century has new shrines which their medieval churches never knew. East Anglia has not just these shrines, plus all the renewed pilgrim activity at Walsingham, but also the church of St Julian in Norwich, which is now very much a shrine to its most famous inhabitant:

This is a reconstruction of Julian's cell, which was destroyed by bombing. When Julian of Norwich was an anchoress here we know that people came to seek her out, but that was because they wanted the wisdom of the living woman - not to make pilgrimage to a saint. No one in the Middle Ages would have brought offerings or lit candles at Julian's shrine, but since the twentieth century pilgrims have been doing those things in this little suburban church. They buy hazelnuts, as pilgrim tokens.

From East Anglia let's move swiftly on into Kent (skipping over London, because I can't afford to visit St Edward's shrine at Westminster Abbey...). Canterbury Cathedral, of course, provides several examples, as one of medieval Europe's most popular shrines and pilgrimage destinations. The empty space once occupied by the shrine of St Thomas Becket is marked by a single candle in the lofty east end of the cathedral:

The little candle is dwarfed by the space, and it's a powerful memorial. All this part of the cathedral was rebuilt to house St Thomas' shrine - the pillars are red marble as an allusion to his holy blood, and all the windows (treasures of thirteenth-century art) depict his miracles. Those windows tell lively stories of people from all classes who sought out the shrine of St Thomas for healing and help, but the shrine to which they came is gone.

The site of his martyrdom is also dramatically highlighted, and made a place for prayer:

As well as these points for devotion to St Thomas, in the crypt there is an atmospheric space set aside for prayer, dedicated to Our Lady of Canterbury:

As you can see, visitors are encouraged to light candles and take prayer cards here, and there's a beautiful statue made in 1982. It's a wonderfully quiet space in the middle of a cathedral almost always full of tourists ('from every shire's end...'). One thing I do find odd about Canterbury Cathedral, though, is how much Thomas Becket overshadows its other saints - the Anglo-Saxon archbishops Dunstan and Alphege had shrines near the high altar too, but you can't find those sites unless you're specifically looking for them. St Anselm has a chapel, but there are no prayer cards or candles for him. An interesting choice of priorities, reflecting which saints are popular today (and in the late Middle Ages) rather than at other possible points in Canterbury's 1400-year history.

While we're in Canterbury, I ought also to mention one of its other major medieval shrines, lost among the remains of St Augustine's Abbey:

St Augustine of Canterbury, his sainted fellow-missionaries, King Ethelbert, and Bertha of Kent were all buried here, but only concrete blocks mark out the sites of their tombs.

English Heritage do an excellent job presenting the history of this church to the public, but of course it's an archaeological and historical site - not anything close to a shrine. Though it's obvious why they don't encourage visitors to interact with this site in the same way the cathedrals do, it's important to remember that this was once a place of devotion and pilgrimage, just as Canterbury Cathedral was or any of the other churches in this post. The difference between them today is an accident of history, more than anything else.

As an additional note: a shrine to St Augustine has recently been built, along medieval lines, in the church in Ramsgate which is 'England’s newest shrine recalling England’s first missionary': here's a picture.

From Kent into Sussex, and Chichester Cathedral. Above is the site of the shrine of St Richard of Chichester, bishop here in the thirteenth century. It's behind the high altar, and the cathedral website provides a useful guide to the mixture of modern art and medieval devotion here. 'The Shrine of St Richard in Chichester was considered by many to be the third most important in the land after St Thomas in Canterbury and the Virgin Mary at Walsingham, so brought pilgrims to both the city and the cathedral. The gifts they brought to the shrine provided the funds that largely ran the cathedral and enabled refurbishment in those times, as do the gifts of visitors today', it says (a more fair-minded way of talking about pilgrimage-as-fundraising than you sometimes see!). 'The modern area is a raised platform with a Purbeck marble altar designed by Robert Potter in 1984... Behind the altar is a tapestry screen designed by the German artist Ursula Benker-Schirmer in 1985.' The tapestry illustrates some of the miracles of St Richard.

'History repeats itself in the shrine area,' the cathedral website says, 'with treasures for modern pilgrims to see and prayers are given and candles lit exactly as medieval pilgrims did in the past.'

And indeed they are, in large numbers - each one the flame of a prayer, or an individual's thought.

We've already seen a Wessex shrine at Winchester, where candles burn for St Swithun; but it's also worth mentioning one of Wessex's shrines which is now in ruins. Above are the remains of Shaftesbury Abbey, where the Anglo-Saxon saint Edward the Martyr was buried. It's a museum now, a very nice one, and here (unlike at St Augustine's in Canterbury) there's an effort to suggest a church within the ruins:

Three more examples. First, Worcester Cathedral, once home to two medieval saints, St Oswald of Worcester and St Wulfstan. By one of the ironies of history, the space near the high altar which once held their shrines is now home to a very different kind of draw to the tourists:

In the centre here is the tomb of King John, who is here because he wanted to be buried near to the shrines of Wulfstan and Oswald. Their tombs are gone and his remains, one of the cathedral's main tourist attractions; between this and Katherine of Aragon, it seems that royal tombs play some of the same role within cathedrals as saints' tombs once did. Worcester doesn't attempt to reconstruct St Wulfstan's shrine or point out where it might have been, but they do give space to remember the saint in the eleventh-century crypt:

They also have (or did when I was there last year; I don't know if it's permanent) a fantastic exhibition on the medieval history of the cathedral, including images of manuscripts produced at the monastery, quotations from Old English texts and reflections on Anglo-Saxon spirituality. But no 'shrine' as such.

Finally, into Oxfordshire. Þonne resteð Sancta Fryðeswyð on Oxnaforda, 'St Frideswide rests at Oxford', says the 'List of Saints' Resting Places'; centuries before Oxford had a university, it had St Frideswide and her shrine. The Priory of St Frideswide was seized by Thomas Wolsey in 1525, who founded a college on the site which became Christ Church, one of the richest of Oxford's colleges. The church of the priory is Oxford Cathedral, which has a monument to the shrine on whose destruction its wealth was built:

(You'd really think I would have a picture of this in daytime, but apparently I don't!) This chapel is in the north-east corner of the cathedral, and is frequently used a site for modern art inspired by Frideswide's story - it also has a Burne-Jones window showing Frideswide's life in vivid colour.

And finally a shrine which brings us full circle. This is Dorchester Abbey in Oxfordshire, which has a modern reconstruction of the shrine of its Anglo-Saxon bishop, St Birinus:

In the Middle Ages Birinus was also venerated in Winchester, and in front of the shrine of St Swithun in Winchester Cathedral, with which we began, there is a fragment of the medieval shrine of St Birinus encased in a cross:

The inscription reads 'The fragments of the Shrine of Birinus, first Bishop of Dorchester, set in this cross, were given by Dorchester Abbey to commemorate the 1300th anniversary of the transfer of the See of Wessex from Dorchester to Winchester, 1979'. The shrine itself has become a relic.

In some ways these pictures speak for themselves, but I'll just say a few things in closing. Firstly, I think all this is admirable and worthy of praise; I complain every now and then about negative portrayals of medieval religion, and there's no doubt that just dismissing medieval shrines as silly superstition is by far the easiest attitude to take. But these are all examples (and fairly recent examples, mostly from the past few decades) of churches engaging seriously and sensitively with their medieval history, and being open to seeing the good in it. They embrace saints as their founders or as significant figures in their history, and find them useful as a means of telling stories about their past. One reason I included the quotations from the 'List of Saints' Resting Places' is to make the point that these are ancient shrines - many of them date back to the seventh or eighth century, and in most cases the medieval history of these churches 'outweighs', in simple temporal measure, their post-Reformation history: some of them had been in existence for eight hundred years or more before the Reformation, which is only five hundred years ago. It's easy from a modern perception to elide all that time - it's all just the Dark Ages, isn't it? Just mud and darkness. But eight hundred years is a very long time. We are closer in time to the Reformation than sixteenth-century pilgrims were to the Anglo-Saxon saints whose relics they venerated, and that ought to put into perspective the modern tendency to assume everything 'medieval' is all just basically the same.

And secondly, I admire the willingness of these churches to see and point out parallels between medieval pilgrims and their own twenty-first century visitors. It's so common to see medieval pilgrims treated as 'other', as stereotypes, as fools or dupes whose devotions deserve only to be joked about or cynically explained away. (All about greedy monks and money-raising, right?) This is a popular media perception, but these modern shrines - or memorials to shrines - suggest that many ordinary people do not find the practices of medieval devotion as utterly alien as this perception would suggest. Of course, modern visitors don't interact with shrines in the same ways medieval pilgrims did, and the absence of physical relics does make a big difference. But not perhaps as much as you might think. Who knows what the people who visit the shrines to St Chad or St Etheldreda or St Swithun think about when they light candles in these places? I wouldn't presume to guess. Many probably think of themselves as tourists, not as pilgrims, and light a candle as a nice thing to do; others do it with clear intention and particular prayers in mind. No one does it because they're expected to - it's entirely a personal choice. Are the hopes, desires, and fears which those candle flames represent really so different from those of medieval pilgrims, even if the beliefs which structure them have changed? There are now, as there were in the Middle Ages, a variety of ways for people to interact with these holy places, and the beliefs people bring to them vary. But the very fact that these spaces are made the focus of attention and reflection, and prayer, means that there is some kinship. In one sense these shrines are lost, destroyed - they are absences, as I began by saying. But they aren't actually empty; they are, to visitors today as in the Middle Ages, full of meaning.

Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this excellent post.

ReplyDeleteMight I offer a couple of corrections.

First, the surviving screen at Crowland is not the reredos of the high altar, but rather the nave screen that once separated the parochial precinct from the monastic precinct. The altar between the lateral doors would have been the parish altar, likely dedicated to the Holy Cross. The nave itself survived the crimes of Cromwell’s men in the Dissolution, but it was not so lucky under the other Cromwell in the English Civil War. His soldiers did great damage to the nave, and it subsequently deteriorated into ruin. The monastic precinct, where once stood the quire and sanctuary, reredos and shrine, is now a graveyard, stretching far east of the nave screen.

Second, there are two shrines in England that are not empty. One is St Alban’s. The shrine structure itself was fully restored some time ago, but it was empty of any relics for many years. But in 2002, a clavicle from the saint’s remains was presented to the cathedral by the church of St Pantaleon in Cologne, Germany, where the saint’s relics had apparently been sent for safekeeping. At the time of the Dissolution, both St Alban’s cathedral and St Pantaleon’s church were Benedictine monasteries.

The other not-empty shrine is that of St Wite (Latin, St Candida) at Whitchurch Canonicorum in Dorset. It is the only shrine to survive the Dissolution and the Civil War unspoiled. The shrine structure is in the old foramina style, quite unlike the later shrines you show in this post. It is unusual in having the coffin over the prayer-holes rather than under them.

Fantastic post. Thank you. I spent a three month sabbatical earlier this year investigating (in a rather haphazard way) the way communities tell the stories of their local saints, both in the UK and in countries which hadn't had their shrines swept away by the Reformation, in particular Sardinia and Sicily. We went to Cagliari for the wonderful festival of St Efisio, and joined in the procession in his honour. What struck me most powerfully was the sense of genuine affection for the local saint, which centred around the statue of him which was carried in a gilded ox cart the 30 km or so from Cagliari to the place of his martyrdom on a beach outside the capital. The people next to us in the crowd, when the moment came for the statue to appear at the end of the procession, whispered excitedly "The saint is coming, the saint is coming!" https://localsaints.blogspot.com/p/santephisio.html .

ReplyDeleteI was reminded of Eamonn Duffy's description of the effect of the destruction of the shrines to the saints in Morebath (Voices of Morebath) " “all those tokens of the tenderness and hope which Morebath had invested in its saints were now expressly declared to be unchristian, and placed outside the law.” "Tokens of tenderness and hope" seems to me to sum it up.

It is good to see some parts of the C of E at least rediscovering that need for "tokens of tenderness and hope", and recognising that people need sacred places and material ways of worshipping that bypass and transcend words.