Æthelred (CUL MS. Ee 3.59, f.3v)

Ða gelamp hit þæt se cyning æþelred forðferde ær ða scypo comon, he geendode his dagas on Sancte Georgius mæssedæg æfter myclum geswince 7 earfoðnyssum his lifes. 7 þa æfter his ende ealle þa witan þe on Lundene wæron 7 seo buruhwaru gecuron Eadmunde to cyninge, 7 he his rice heardlice wærode þa hwila þe his tima wæs. Þa comon þa scipo to Grenawic to þam gandagum, 7 binnan litlan fæce wendon to Lundene 7 dulfon þa ane micle dic on suðhealfe, 7 drogon hera scipo on westhealfe þære bricge, 7 bedicodon þa syððan, 7 þa buruh utan, þæt nan man ne mihte ne inn ne ut, 7 oftrædlice on þa buruh fuhton, ac hi him heardlice wiðstodon. Þa wæs Eadmund cyng ær þan gewend ut 7 geard þa Westseaxon, 7 him beah eall þæt folc to.

'Then it happened that King Æthelred died before the ships came. He ended his days on St George’s Day, after great labour and difficulties in his life. And then after his death all the witan who were in London, and the garrison, chose Edmund as king, and he held his kingdom stoutly while his time lasted. Then the ships came to Greenwich during the Rogation Days, and within a short time turned to London and dug a great ditch on the south side, and dragged their ships to the west side of the bridge, and then built a dyke around the town so that no one could get in or out. They frequently attacked the town, but it stoutly withstood them. King Edmund had previously got out, and went to Wessex, and all the people there submitted to him.'

This is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's description of the events of April-May 1016, picking up where we left it a month ago. After Cnut had obtained the submission of the north, by fair means or foul, the war shifted south again to London, where King Æthelred had been holed up for the past few months. And there he died, on St George's Day, after a reign of 38 years (minus one brief interruption) - one of the longest reigns of any English monarch, despite all his 'labour and difficulties'.

With hindsight, it seems especially ironic to a modern reader that Æthelred, remembered to history as the 'unready' unwarlike king, should die on the feast of such a martial saint. However, St George was not, of course, England's patron saint in the Anglo-Saxon period, so the irony would perhaps not have been so apparent to an eleventh-century reader. But there's plenty of hindsight at play already in this entry, which was clearly written not just after Æthelred's death but after the death of Edmund, too. We get here comments which serve almost as epitaphs for the two kings: Æthelred and Edmund respectively had 'great labour and difficulties in his life' and 'held his kingdom stoutly while his time lasted' - pretty kind judgements, really, especially when compared with the kind of epitaph Æthelred was getting a century or so later (this is from John of Worcester):

At that time, on Monday, 23 April, in the fourteenth indiction, Æthelred, king of the English, died, after the great toils and many tribulations of his life. These St Dunstan had prophetically announced could come upon him when he, on the day of his coronation, had placed the crown upon his head: ‘Because,’ he said, ‘you obtained the kingdom through the death of your brother, whom your mother killed; hear therefore the word of the Lord. Thus saith the Lord, ‘The sword shall not depart from thine house, raging against thee all the days of thy life’, slaying those of your seed until your kingdom is given to an alien power whose customs and tongue the people you rule do not know; and your sin and your mother’s sin and the sin of the men who committed murder at the wicked woman’s advice will not be expiated except by long-continued punishment.’ His body was honourably buried in the church of St Paul the Apostle.

The Chronicle of John of Worcester, ed. and trans. Jennifer Bray and P. McGurk (Oxford, 1995) vol. ii, p.485.

This prophecy, which in this storming Old Testament form derives from the fertile imagination of Dunstan's hagiographer Osbern of Canterbury, literally became poor Æthelred's epitaph. Æthelred was buried at St Paul’s (where the most recent high-profile victim of the Vikings, St Ælfheah, also lay), and by the later medieval period his tomb had an inscription quoting Dunstan's prophecy. The tomb was destroyed in 1666 in the Great Fire of London, but the inscription can be read here, and it looked like this:

Anyway, very soon after Æthelred's death the Danish army set about to besiege London. They arrived during the Rogation Days, the three days before Ascension Day, which were on 7-9 May in 1016. They dragged their ships to the west of London Bridge, presumably because the bridge itself was heavily defended, and then bedicodon 'bedyked' the city.

At this point we can return to a source which has been absent from this series for a while, the Encomium Emmae Reginae. The Encomium (as a reminder) was written in 1041-2 for Queen Emma, who was by then Cnut's widow, though in 1016 she was newly Æthelred's. It's been suggested that Emma herself was in London during the siege, though if that was the case it isn't mentioned in the Encomium. Its chronology of this period is a bit confused, but it does describe the siege of London, saying that Cnut

Encomium Emmae Reginae, ed. and trans. Alistair Campbell (London: Royal Historical Society, 1949), pp. 23-5.

ordered the city of London, the capital of the country, to be besieged, because the chief men and part of the army had fled into it, and also a very great number of common people, for it is a most populous place. And because infantry and cavalry could not accomplish this, for the city is surrounded on all sides by a river, which is in a sense equal to the sea, he caused it to be shut in with towered ships, and held it in a very strong circumvallation.

And so God, who wishes to save all men rather than to lose them, seeing these natives to be pressed by such great danger, took away from the body the prince who was in command of the city within, and gave him to everlasting rest, that at his decease free ingress might be open to Knútr, and that with the conclusion of peace the two peoples might have for a time an opportunity to recover. And this came to pass. For the citizens, having given their prince honourable burial, and having adopted a sound plan, decided to send messengers and intimate their decision to the king, that is to say, that he should give them his pledge of friendship, and should take peaceful possession of the city. This occurred at a time when it seemed acceptable enough to Knútr, and a treaty was made, a day being arranged for his entry.

But part of the garrison spurned the decision of the citizens, and in the night preceding the day on which the king made his entry, left the city secretly with the son of the deceased prince, in order to collect a very large force again, and try if they could perhaps expel the invading king from their country. And they did not rest till they had assembled nearly all the English who were still inclined to them rather than to Knútr. Knútr, however, entered the city and sat on the throne of the kingdom. But he, nevertheless, did not believe that the Londoners were yet true to him, and, accordingly, he had the equipment of his ships renewed that summer, lest if the army of his foes happened to besiege the city, he should be delivered by the foes within to those without and perish. Guarding against this, he again retired for the moment like a wise man, and having gone on board his ships, he left the city and went to the island called Sheppey with his followers, and wintered there, peacefully awaiting the outcome of the matter.

And so Eadmund - for so the youth who had collected the army was called - when Knútr retired, came with an army not insignificant but immense, and entered the city in state. Soon all followed him, obeyed him, and bestowed their favour upon him, and urged him to be a bold man, declaring that he rather than the prince of the Danes was their choice.

Note that the Encomium - notoriously - does not name Æthelred, 'the prince who was in command of the city', even though he was the first husband of the woman for whom this text was written. Apparently Emma preferred not to mention him; but Edmund (her stepson) is described favourably here and throughout the account of Cnut's invasion.

Viking weapons of this date found in the Thames near London Bridge (Museum of London)

Despite what the Encomium says, Cnut did not enter London at this point; the Danish army besieged London on at least three separate occasions in the summer of 1016, and never captured it (each time ‘Almighty God rescued it’, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says). But the Danes don’t seem to have regarded this as a failure, at least judging by the skaldic poems, which are jubilant about the attacks on London. The anonymous poem Liðsmannaflokkr, ostensibly the voice of a rank-and-file soldier fighting among the Danish army during the siege, adds a splash of brilliant colour to the more sober accounts above. Here are one or two highlights (from this site, where you can find the whole poem):

Gǫngum upp, áðr Engla

ættlǫnd farin rǫndu

morðs ok miklar ferðir

malmregns stafar fregni.

Verum hugrakkir hlakkar;

hristum spjót ok skjótum;

leggr fyr órum eggjum

Engla gnótt á flótta.

Let us go ashore, before the staves of the metal-rain [BATTLE > WARRIORS] and large militias of killing learn that the ancestral lands of the English are traversed with the shield. Let us be brave-minded in battle; let us brandish spears and shoot [them]; an ample number of the English takes to flight before our blades.

Margr ferr Ullr í illan

oddsennu dag þenna

frár, þars fœddir órum,

fornan serk, ok bornir.

Enn á enskra manna

ǫlum gjóð Hnikars blóði...

Many a fierce Ullr

Knútr réð ok bað bíða

(baugstalls) Dani alla;

(lundr gekk rǫskr und randir

ríkr) vá herr við díki.

Nær vas, sveit þars sóttum,

Syn, með hjalm ok brynju,

elds sem olmum heldi

elg Rennandi kennir.

Knútr decided and commanded all the Danes to wait; the mighty tree of the ring-support [SHIELD > WARRIOR = Knútr] went, brave, under the shields; the army fought by the moat. Syn [lady], it was nearly as if the master of the fire of Rennandi

Út mun ekkja líta

— opt glóa vôpn á lopti

of hjalmtǫmum hilmi —

hrein, sús býr í steini,

hvé sigrfíkinn sœkir

snarla borgar karla

— dynr á brezkum brynjum

blóðíss — Dana vísi.

The chaste widow who lives in stone will look out — weapons often glint in the air above the helmet-wearing ruler — [seeing] how the victory-avid leader of the Danes [DANISH KING = Knútr] attacks sharply the men of the city; the blood-ice [SWORD] clangs against British mail-shirts.

Hvern morgin sér horna

Hlǫkk á Tempsar bakka

— skalat Hanga má hungra —

hjalmskóð roðin blóði.

Every morning the Hlǫkk

‘holding a maddened elk’ – you don’t get that in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle! Amazing. Note that the army are fighting við díki, 'by the moat/dyke', with which the Danes had bedyked London. It's been suggested that the 'chaste widow' is Queen Emma herself, looking out from London's stone walls at the valiant young Danish king, while Odin's ravens feed on the blood of the English...

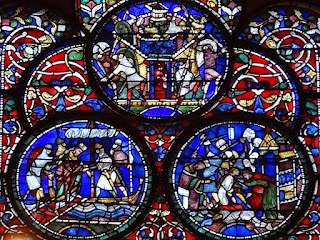

A Viking siege (in this case of Canterbury) from a 12th-century window in Canterbury Cathedral

So Cnut is near London and Edmund is in Wessex, both now accepted as king by some part of the country. We’ll be back at Midsummer for the commencement of some dramatic battles, and the first appearance of Earl Godwine...

1 comment:

Fascinating, as always, especially the different 'versions' of what happened. And thanks for blóðíss. I have been thinking recently about Beowulf 1607-1613.

Þa þæt sweord ongan

æfter heaþoswate hildegicelum,

wigbil wanian. Þæt wæs wundra sum,

þæt hit eal gemealt, ise gelicost,

ðonne forstes bend Fæder onlæteð,

onwindeð wælrapas, se geweald hafað

sæla 7 mæla.

Clearly there's a common idea behind 'hildegicelum' and 'blóðíss.'

Post a Comment