This year Good Friday falls on Lady Day, the feast of the Annunciation. This is a rare occurrence and a special one, because it means that for once the day falls on its 'true' date: in patristic and medieval tradition, March 25 was considered to be the historical date of the Crucifixion. It happens only a handful of times in a century, and won't occur again until 2157.

These days the church deals with such occasions by transferring the feast of the Annunciation to another day, but traditionally the conjunction of the two dates was considered to be both deliberate and profoundly meaningful. The date of the feast of the Annunciation was chosen to match the supposed historical date of the Crucifixion, as deduced from the Gospels, in order to underline the idea that Christ came into the world on the same day that he left it: his life formed a perfect circle. March 25 was both the first and the last day of his earthly life, the beginning and the completion of his work on earth. The idea goes back at least to the third century, and Augustine

explained it in this way:

He is believed to have been conceived on the 25th of March, upon which day also he suffered; so the womb of the Virgin, in which he was conceived, where no one of mortals was begotten, corresponds to the new grave in which he was buried, wherein was never man laid, neither before him nor since.

This day was not only a conjunction of man-made calendars but also a meeting-place of solar, lunar, and natural cycles: both events were understood to have happened in the spring, when life returns to the earth, and at the vernal equinox, once the days begin to grow longer than the nights and light triumphs over the power of darkness. Here's Bede explaining some of the symbolism of this latter point (from

here, p.25):

It is fitting that just as the Sun at that point in time first assumed power over the day, and then the Moon and stars power over the night, so now, to connote the joy of our redemption, day should first equal night in length, and then the full Moon should suffuse [the night] with light. This is for the sake of a certain symbolism, because the created Sun which lights up all the stars signifies the true and eternal light which lighteth every man that cometh into the world, while the Moon and stars, which shine, not with their own light (as they say), but with an adventitious light borrowed from the Sun, suggest the body of the Church as a whole, and each individual saint. These, capable of being illumined but not of illuminating, know how to accept the gift of heavenly grace but not how to give it. And in the celebration of the supreme solemnity, it was necessary that Christ precede the Church, which cannot shine save through Him... Observing the Paschal season is not meaningless, for it is fitting that through it the world's salvation both be symbolized and come to pass.

As Bede says at the end here, this dating is symbolic but it is not

only a symbol; it reveals the deep relationship between Christ's death and all the created world, including the sun and moon and everything on earth. According to some calculations 25 March was also considered to be the eighth day of the week which saw the creation of the world (for more on that, see

this post), as well as the date of certain events from the Old Testament which prefigured Christ's death, including the sacrifice of Isaac and the crossing of the Red Sea. It is the single most significant date in salvation history, and for that reason has also made it into some fictional history too: those of you who are Tolkien fans will know that the final destruction of the Ring takes place on 25 March, to align Tolkien's own eucatastrophe with this most powerful of dates.

But it's the link between the Annunciation and the Crucifixion which has most fascinated theologians and artists over the centuries. Here's one beautiful passage from the Old English Martyrology, in its entry for March 25, explaining what was by the ninth century the common understanding of the date (the text is from

this edition, pp.72-7, with my translation):

On ðone fif ond twentegðan dæg þæs monðes com Gabrihel ærest to Sancta Marian mid Godes ærende, ond on ðone dæg Sancta Maria wæs eacen geworden on Nazareth ðære ceastre þurh þæs engles word ond þurh hire earena gehyrnesse, swa þas treowa ðonne hi blostmiað þurh þæs windes blæd.... Ond ða æfter twa ond ðritegum geara ond æfter ðrym monðum wæs Crist ahangen on rode on ðone ylcan dæg. Ond sona swa he on ðære rode wæs, ða gescæfta tacnedon þæt he was soð God. Seo sunne asweartade, ond se dæg wæs on þeostre niht gecierred fram midne dæg oð non.

On the twenty-fifth day of the month Gabriel first came to St Mary with God’s message, and on that day St Mary conceived in the city of Nazareth through the angel’s word and through the hearing of her ears, like trees when they blossom at the blowing of the wind... And then after thirty-two years and three months Christ was crucified on the cross on the same day. And as soon as he was on the cross, creation revealed that he was truly God: the sun grew black, and the day was turned into dark night from midday until the ninth hour.

At the Annunciation Mary becomes like the blossoming trees in spring, and like the tree which became Christ's cross: she bears new life to the world. The parallel reflects the ancient tradition which links Mary with scriptural images of the tree or the vine, frequently used in the liturgy on feasts of the Virgin -

this, for instance. She is the

root of Jesse from which grows the rod, the

virgo who bears the

virga. And if she is the vine and the tree, she is like the cross - most honoured among human beings and closest to Christ, as the tree of the cross is the most honoured among creatures of the natural world. (For a fascinating discussion of this imagery in light of the link between Mary and the tree/cross in the Anglo-Saxon poem

The Dream of the Rood, see

this book.) The later medieval hymn

Lignum vitae quaerimus muses on the parallel:

Lignum vitae quaerimus,

Qui vitam amisimus

Fructu ligni vetiti...

Fructus, per quem vivitur,

Pendet, sicut creditur,

Virginis ad ubera,

Et ad crucem iterum

Inter viros scelerum

Passus quinque vulnera.

Hic virgo puerpera,

Hic crux salutifera,

Ambe ligna mystica;

Haec hysopus humilis

Illa cedrus nobilis,

Utraque vivifica.

We seek the tree of life,

We who lost life

Through the fruit of the forbidden tree...

The fruit which gives life

Hangs, as we believe,

Upon the Virgin's breast,

And again upon the cross

Between two thieves,

Pierced with five wounds.

Here, the child-bearing Virgin,

Here, the saving cross;

Both are mystic trees.

[The cross], the humble hyssop,

She, the noble cedar,

And both life-giving.

The name 'MARIA' as a tree bearing the fruit 'love', from a 15th-century English manuscript, BL Add. 37049, f. 26

With Mary's

Ave from the angel at the Annunciation began the work of redemption completed on Good Friday; and so, as many medieval writers note, her answer makes her the inverse of

Eva, the means by which Eve’s sin is turned to good. In the Old English Martyrology, the next entry describes how on 26 March Christ descended into hell, to save Adam and Eve and all those who had died before his coming. Eve appeals to him by merit of her kinship with Mary:

Đær hine eac ongeaton Adam ond Eua, þær hi asmorede wæron mid deopum ðeostrum. Đa ða hi gesawon his þæt beorhte leoht æfter þære langan worolde, þær Eua hine halsode for Sancta Marian mægsibbe ðæt he hire miltsade. Heo cwæþ to him: ‘Gemyne, min Drihten, þæt seo wæs ban of minum banum, ond flæsc of minum flæsce. Help min forþon.’ Đa Crist hi butu ðonan alysde ond unrim bliðes folces him beforan onsende, ða he wolde gesigefæsted eft siðian to þæm lichoman.

Adam and Eve saw him there too, where they were stifled in deep darkness. When they saw his bright light, after that long age, Eve implored him there for the sake of her kinship with St Mary to have mercy on her. She said to him: ‘Remember, my Lord, that she was bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh. Help me for that reason!’ Then Christ released them both from that place and also sent a countless number of joyful people before them, when, triumphant, he set out to return to his body.

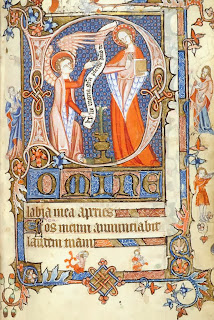

The traditional pairing of the Annunciation and the Crucifixion means that the two scenes are often depicted together in medieval art, as above in a fourteenth-century manuscript, and in the image at the top of this post. The first example from England is probably the one found on the eighth-century

Ruthwell Cross, where a depiction of the Crucifixion was added directly below the Annunciation scene some time after the original design was completed:

Some six hundred years later, artists were still finding new ways to explore this conjunction. Towards the end of the fourteenth century, the idea inspired the development of a distinctive and beautiful image found almost uniquely in English medieval art: the lily crucifix. This iconography combines the Annunciation and the Crucifixion by depicting Christ crucified on a lily amid an Annunciation scene. The lily is the symbol of Mary, of course, and is often referenced in depictions of the Annunciation and in poetry about the Virgin; this idea grafts that flower imagery into the tradition which links Mary to the root of Jesse and the tree of the cross. Here's a gorgeous example of a lily crucifix from a Welsh manuscript, the

Llanbeblig Hours, made at the end of the fourteenth century:

The Virgin sits under a green canopy, while Gabriel in green and red kneels

facing her.

Another slightly later manuscript image can be seen

here, but the lily crucifix is found in all kinds of media - there are estimated to be 19 surviving examples in all, ranging from painted screens and stained glass to carvings on stone tombs, misericords and wall-paintings. Here's a painted ceiling from the Lady Chapel of St Helen's Church, Abingdon, with the lily bearing the crucified Christ between Mary and the angel:

The rest of this impressive ceiling, which dates from c.1390, depicts the ancestors of Christ in a form of Jesse Tree. There are more pictures

here.

Not far away in Oxford, there's a beautiful stained glass window of a lily crucifix in the church of St Michael at the Northgate:

This too was originally part of an Annunciation scene, though the other panels are now lost.

And here's a wonderful example in alabaster,

now in the V and A, where a giant lily-stem carrying Christ soars right up into heaven:

Click to zoom in and study the detail! The top half of the panel is damaged, but clearly showed God the Father holding the crucified Christ, part of a common depiction of the Trinity - compare the image at the top of this post, and there are more examples collected

here.

The lily cross flanked by two figures, Mary and the angel, offers a visual parallel to the usual Crucifixion scene, where Christ on the cross is attended by Mary and St John. One of the ways in which medieval Christians were most often encouraged to approach the Passion was by imagining and entering into Mary's emotions, to see Christ, as his mother might, as a vulnerable human child even at the moment of his death as an adult. There are many superb examples of poetic meditations on this subject -

here's a particularly moving one, and more can be found

here. This four-line poem is one of the best-known:

Nou goth sonne under wod,

Me reweth, Marie, thi faire rode.

Nou goth sonne under tre,

Me reweth, Marie, thi sone and thee.

[Now goes the sun under the wood,

I grieve, Mary, for your fair face;

Now goes the sun under the tree,

I grieve, Mary, for thy son and thee.]

Although so short and apparently so simple, this is full of meaningful wordplay: as the sun sets behind the wood, so Christ the Son is shrouded in darkness on the wood of the cross, the tree.

Rode can mean both 'face', and rood, of course.

Another good example of a text which approaches the Passion through Mary's motherhood is

'Stond wel, Moder, under rode', with its explicit appeal to a female audience and its poignant comment that by her grief Mary learns to understand 'what pain they have that children bear'. In this poem Mary's situation, though so extraordinary, gives her kinship with all women who have lost children or found in motherhood grief as well as joy. The link between the Annunciation and the Crucifixion brings together in one circle the beginning and the end of Mary's motherhood, its joy and its sorrow, as well as completing the circle of Christ's life on earth.

However, although the Annunciation and the Crucifixion are so closely linked, they don't often occur on the same day. Good Friday fell on March 25 in 1608, too, when John Donne wrote this poem on the occasion:

Upon the Annunciation and Passion Falling upon One Day

1608

Tamely, frail body, abstain today; today

My soul eats twice, Christ hither and away.

She sees Him man, so like God made in this,

That of them both a circle emblem is,

Whose first and last concur; this doubtful day

Of feast or fast, Christ came, and went away.

She sees Him nothing twice at once, who’s all;

She sees a Cedar plant itself and fall,

Her Maker put to making, and the head

Of life at once not yet alive, yet dead;

She sees at once the virgin mother stay

Reclused at home, public at Golgotha;

Sad and rejoiced she’s seen at once, and seen

At almost fifty and at scarce fifteen;

At once a Son is promised her, and gone;

Gabriel gives Christ to her, He her to John;

Not fully a mother, she’s in orbity,

At once receiver and the legacy.

All this, and all between, this day hath shown,

The abridgement of Christ’s story, which makes one

(As in plain maps, the furthest west is east)

Of the Angel’s Ave and Consummatum est.

How well the Church, God’s court of faculties,

Deals in some times and seldom joining these!

As by the self-fixed Pole we never do

Direct our course, but the next star thereto,

Which shows where the other is, and which we say

(Because it strays not far) doth never stray,

So God by His Church, nearest to Him, we know

And stand firm, if we by her motion go.

His Spirit, as His fiery pillar doth

Lead, and His Church, as cloud, to one end both.

This Church, by letting these days join, hath shown

Death and conception in mankind is one:

Or 'twas in Him the same humility

That He would be a man, and leave to be:

Or as creation He had made, as God,

With the last judgment but one period,

His imitating Spouse would join in one

Manhood’s extremes: He shall come, He is gone:

Or as though one blood-drop, which thence did fall,

Accepted, would have served, He yet shed all,

Or as though the least of His pains, deeds, or words,

Would busy a life, she all this day affords;

This treasure then, in gross, my soul uplay,

And in my life retail it every day.

A paradoxical conjunction of feast and fast: was there ever a day more suited to metaphysical poetry? Although this wonderful poem is all so characteristically Donne, it explores many of the same parallels as the medieval texts and images we've already seen: the circle, the tree, beginnings and endings, and the two moments in the life of the Virgin, seen at once 'at almost fifty and at scarce fifteen'.

The coincidence of feasts gains rather than loses from being a rare occurrence, as Donne suggests - from falling 'some times and seldom'. It is, he says, an act of wisdom in the church, existing in time, to be moveable, while God is a fixed star, eternally the same. The overlapping cycles of the church's calendar offer many such conjunctions, which change every year as the fixed cycle intersects with the variable one. Although these coincidences often have their origin as much in pragmatic decisions about the calendar as in theology, with the kind of approach Donne exemplifies here they can be read in meaningful and imaginative ways. Through such eyes, a meeting of feasts like this year's is not exactly a coincidence, but perhaps one of those 'occasional mercies' of which Donne writes

elsewhere: 'such mercies as a regenerate man will call mercies, though a natural man would call them accidents, or occurrences, or contingencies'. They are moments which seem to reveal a purpose behind the randomness of life, to show both natural and man-made events and seasons to be part of an ordered and carefully structured universe. It's the calendrical equivalent of a pun, like the medieval poet's 'sun under wood' or Donne's

orbity - a place where meanings meet.

This year's conjunction is a particularly rich example, but all through the year these coincidental graces can be found, as beauty and meaning are produced by the changing juxtaposition of feasts and fasts, the fixed and the moveable seasons. Lent, Easter, Ascension Day, Whitsun - all can at various times coincide with different fixed occasions, different stages in the seasons of spring and summer, and the experience of each can accordingly change from year to year. As the cycles intersect in different ways, familiar texts and images breathe new life into each other, and bring forth new and different fruit (to borrow the Old English Martyrology's metaphor for Mary's conception). In such ways the interlocking wheels of the calendar give cosmic meaning to the cycle of our own days, months, and years.

Of course, a fixed date of Easter would do away with all this. As a medievalist, I found the

discussion of the question of fixing a date for Easter a few months ago rather depressing. If there were any theological arguments under consideration, no one seemed to think it worthwhile to articulate them publicly; discussion focused mostly on solving the non-existent problem that some people (schools, maybe?) apparently find a movable date for Easter a bit inconvenient. I've never in my life heard

anyone complain about being inconvenienced by the date of Easter, so I really struggle to imagine who considers this a pressing issue. And for that, churches would break with nearly two thousand years of tradition, a complex system worked out with great care and thought and invested over centuries with profound meaning.

The fixed dates proposed for Easter are in April, so never again would Good Friday fall on the feast of the Annunciation. So much loss for so little gain!

Bede truly would be

spinning in his grave. It strikes me (once again) that however much many people today, in their ignorance of all but the broadest stereotypes about the Middle Ages, stigmatise the medieval church as worldly, rigid, and oppressive, it was in some ways immeasurably more humane and creative than its modern successors. It was happy to see human life as fully part of the natural world, shaped by the cycles of the sun and moon and the seasons; it was able to articulate a belief that material considerations, convenience, and economic productivity are not the highest goods, and not the only standards by which life should be lived. When confronted by calendar clashes with the potential to be a little awkward or inconvenient, the medieval church could have the imagination not to simply suppress them or tidy them away, but to find meaning in them - meaning which springs from deep knowledge of the images and poetry of scripture, the liturgy, and popular devotion.

So enjoy the coincidence this year, this meeting of dates which has inspired preachers, poets, and artists through many centuries of Christian tradition. Unless you plan to live until 2157, you won't see another in your lifetime - and if the date of Easter is fixed, it will never happen again.