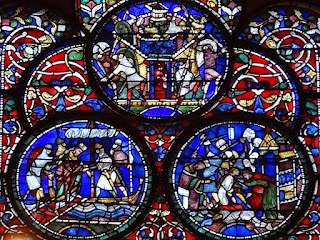

The giving of the law to Moses, next to Pentecost in a 'typological picture-book', c.1405 (BL King's 5, f. 27)

This year we have been living through a rare series of dates which would have delighted a medieval expert on the calendar. As I discussed a few months ago, Good Friday fell this year on March 25, which was traditionally believed to be the historical date of both the Crucifixion and the Annunciation. All subsequent dates which are dependent on Easter have therefore also fallen this year on their 'true' dates, including the Feast of the Ascension (May 5) and tomorrow's feast, Pentecost, which is on its supposed historical date of May 15.

From an early date in church tradition, other important events in salvation history were aligned with these significant dates, with which they were typologically linked: March 25 was said to be not only the date of the Crucifixion and the Annunciation to Mary, but also Old Testament events which foreshadowed Christ's death, such as Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac, the crossing of the Red Sea, and so on. However, from the very beginning Pentecost already commemorated two anniversaries which link the Old Testament and the New: it takes its date from the Jewish festival celebrated fifty days after Passover, marking the day when the law was revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai, and therefore subsequently the date fifty days after Easter when the Holy Spirit descended on the apostles. It's a double anniversary in more ways than one.

In case it's of interest, here are two short extracts of texts from Anglo-Saxon England which touch on the connection between the Old and New Testament events celebrated at Pentecost. First a section from the Old English Martyrology, in its entry for May 15 (text from here, with my translation):

On þone fifteogðan dæg þæs monðes bið se micla dæg þe is nemned Pentecosten. Se dæg wæs mære on þære ealdan æ ær Cristes cyme, forðon þe on þone dæg God spræc to Moyse of heofonum geherendum eallum Israhela folce. Ond þy dæge God sealde his æ ond his bebodu þæm ylcan folce on twam stænenum bredum awritene on Sinai þære dune; ond eft æfter Cristes uppastignesse to heofonum þy ilcan dæge he onsænde his þegnum þone halgan gast, ond ealra þara monna wæs on anum huse hundteontig ond twentig. Þa færinga wæs geworden sweg of heofonum swa swa stranges windes sweg: ond se sweg gefylde þæt hus þær hi sæton, ond ofer heora ælcne onsundran sæt swa swa fyr, ond hi mihton þa sona sprecan on æghwelc þara geþeoda þe under heofonum is; ond þa hælendes þegnas mihtan siððan don heofonlico wundor þurh þone gast. Þæm gaste æghwelc gefullwad man nu onfehð þurh biscopa handa onsetenesse, ond se gast wunað mid æghwelcne þara þe god deð, ond he gefyhð on þæs clænan mannes heortan swa swa culfre, þonne heo baðað on smyltum wætre on hluttere wællan.

On the fifteenth day of the month is the great day which is called Pentecost. This day was celebrated in the Old Law before Christ’s coming, because on this day God spoke to Moses from heaven, in the hearing of all the people of Israel. And on this day God gave his law and his commandments to that people, written on two stone tablets, on the mountain of Sinai. And again, after Christ’s ascension into heaven, on that same day he sent the Holy Spirit on his followers, and all the people who were in the house, one hundred and twenty. Then suddenly there came a noise from heaven like the noise of a strong wind, and the noise filled the house where they were sitting, and over each of them individually there rested something in the likeness of fire. And at once they were able to speak in every one of the languages which are under heaven, and the Saviour’s followers were afterwards able to perform heavenly miracles through that spirit. Every baptised person now receives that Spirit through the laying-on of the bishop’s hands, and the Spirit dwells with all those who do good; and it rejoices in the heart of the pure man, like the dove when she bathes in quiet water in a clear well-spring.

That last sentence is just beautiful. While the Holy Spirit at Pentecost is a noisy rush of sound and fire (swa swa stranges windes sweg, 'like the noise of a strong wind'), the indwelling Spirit conferred at baptism is calm and peaceful as a dove, bathing in the clear and cleansing waters, which are described as hlutor 'clear, pure, bright'.

Those waters are surely meant to evoke baptism, since Pentecost was traditionally a time when baptisms took place. (The English name for the feast, Whitsun, is often said to derive from the white garments worn by the newly-baptised.) As Bede says in his homily for Pentecost:

In order to stamp the memory of this more firmly on the hearts of believers, a beautiful custom of holy Church has grown up, so that each year the mysteries of baptism are celebrated on this day, and as a result a venerable temple is made ready for the coming of the Holy Spirit upon those who believe and are cleansed at the salvation-bearing baptismal font. In this way we celebrate not only the recollection of a former happening, but also a new coming in the font of the Holy Spirit upon new children by adoption.Bede the Venerable, Homilies on the Gospels: Book Two, Lent to the Dedication of a Church, trans. Lawrence Martin and David Hurst (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1991), pp.170-1.

In his Historia Ecclesiastica, Bede provides some examples of the early Anglo-Saxon church conforming to this practice: the baby girl he calls 'the first of the people of the Northumbrians to be baptised', Eanflæd, daughter of King Edwin of Northumbria and his wife Æthelburh, was baptised with a number of others on Whitsunday in 626.

The Pentecostal dove, from the Benedictional of St Æthelwold (BL Add. 49598, f.67v)

To stay with Bede: the Martyrology's restful image of the dove, bathing in calm joy in the quiet waters of the heart, calls to mind Bede's discussion of 'rest' in his homily for Pentecost. In a virtuoso combination of mathematics and mystery, Bede describes the relationship between the descent of the Spirit and the giving of the Law to Moses, and explains how the number fifty, which establishes both dates, can be interpreted to represent the rest of heaven. After commenting on baptism, he says:

Therefore, you dear ones, be attentive to how the type and figure of the feast of the law is in agreement with our festivity. When the children of Israel had been freed from slavery in Egypt by the immolation of the paschal lamb, they went out through the desert so that they might come to the promised land, and they reached Mount Sinai. On the fiftieth day after the Passover, the Lord descended upon the mountain in fire, accompanied by the sound of a trumpet and thunder and lightning, and with a clear voice he laid out for them the ten commandments of the law. As a memorial of the law he had given, he established a sacrifice to himself from the first-fruits of that year, to be celebrated annually on that day... The law was given on the fiftieth day after the slaying of the lamb, when the Lord descended upon the mountain in fire; likewise on the fiftieth day after the resurrection of our Redeemer, which is today, the grace of the Holy Spirit was given to the disciples as they were assembled in the upper room.He draws a parallel between going 'up' the mountain and the 'upper room'; like Moses and the disciples, anyone who wishes to receive the Spirit must leave behind the things below and ascend to the heights.

Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, framed like a Pentecost scene (BL Sloane 346, f. 36)

Bede goes on:

[It] was not without deep significance that the number fifty was observed in the giving both of the law and of grace. It was on the fiftieth day after Passover that the former was given to the people on the mountain, and the latter to the disciples in the upper room. By this number the long-lasting quality of our future rest was surely being shown, since on this fiftieth day the ten commandments of the law were delivered, and the grace of the Holy Spirit was given to human beings. This was to point out clearly that all who carry out the commands of the divine law with the help of the grace of the Spirit are directing their course toward true rest. In the law, the fiftieth year was ordered to be called the year of jubilee, that is, ‘forgiving’ or ‘changed’. During it the people were to remain at rest from all work, the debts of all were to be cancelled, slaves were to go free, and the year itself was to be more notable than other years because of its greater solemnities and divine praises. Therefore, by this number is rightly indicated that tranquility of greatest peace when, as the Apostle says, at the sound of the last trumpet the dead will rise and we shall be changed into glory. Then, when the labours and hardships of this age come to an end, and our debts, that is all our faults, have been forgiven, the entire people of the elect will rejoice eternally in the sole contemplation of the divine vision, and that most longed-for command of our Lord and Saviour will be fulfilled: Be still and see that I am God.Homilies on the Gospels, trans. Martin and Hurst, pp.171-6.

Since it is only by observance of the heavenly commands and the gift of the Holy Spirit that this stillness and vision of unchangeable Truth is reached, both the law of the ten commandments and the grace of the Spirit were given on that particular one of the days which designates rest. Nor is it to be passed over that this number fifty is appropriate to signify inward tranquility, for it is arrived at by multiplying seven times seven and adding one. Under the law the people were ordered to work for six days and to rest on the seventh, and to plow and reap for six years and desist during the seventh, because the Lord completed the creation of the world in six days and desisted from his work on the seventh. Mystically speaking, we are counselled by all this that those who in this age (which is comprised of six periods) devote themselves to good works for the Lord’s sake are in future led by the Lord to a sabbath, that is, to eternal rest.

The fact that the seven days or years are multiplied by seven indicates the manifold abundance of this rest, in which there will be given to the elect that sublime reward concerning which the Apostle exclaims, Eye has not seen, nor has ear heard, nor has it occurred to the heart of man what things God has prepared for those who love him... The grace of the same Spirit is well described by the prophet as being sevenfold, since it is through his inspiration that one arrives at rest, and in the full partaking of and sight of him true rest is reached...

A person who trusts that he can find rest in the delights and abundance of earthly things is deceiving himself. By the frequent disorders of the world, and at last by its end, such a one is proven convincingly to have laid the foundation of his tranquility upon sand. But all those who have been breathed upon by the Holy Spirit, and have taken upon themselves the very pleasant yoke of the Lord’s love, and following his example, learned to be gentle and humble of heart, enjoy even in the present some image of the future tranquility.

'Seven multiplied by seven suggests the perfection of that rest which will never be brought to an end or marred by any blemish... One is added to seven-times-seven... and thus the number fifty is perfectly completed.’ Such calculations as this don't feature much in sermons today, at least not in any I've ever heard; but if they don't appeal to you, bear in mind that the purpose of such detailed observation of times and dates is explicitly to point beyond time to eternity, to a place where anniversaries, numbers, and calendars are no more. As Bede says in his preceding homily, after explaining the significance of all his complicated fours, sevens, forties, and fifties:

We might be prompted in a pleasing way, by this annual festive celebration, to enkindle our desire always to obtain and hold fast to festal times that are not annual but uninterrupted, not earthly but heavenly. Our true bliss is to be sought not in the present time of our mortality, but in the eternity of our future incorruption – the solemnity where, after all our anguish has ceased, our life will be led totally in the vision and praise of God.

Homilies on the Gospels, trans. Martin and Hurst, p.156.

'The coming of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles', marked on 15 May in a 12th-century calendar

(BL Lansdowne 383, f. 5)

(BL Lansdowne 383, f. 5)

See this post for a Pentecost sermon by Ælfric and some Old English poetry on the gifts of the Spirit, and here for a beautiful Middle English version of 'Veni Creator Spiritus'.