One of the most valued regular contributors to this blog is the prolific Anglo-Saxon monk Ælfric, who lived in the second half of the tenth century. Ælfric is best known for his two great collections of English homilies, which aimed to provide sermons for the whole cycle of the church's year, as well as another large collection of saints' lives - more than 160 homilies in all, which display the full range of his remarkable talents as a communicator. He translates and explains an impressive variety of Biblical extracts, patristic texts, liturgical customs, and historical and theological material of many different kinds. This was an incredibly ambitious project, but it was only one part of Ælfric's extraordinary body of work: he also composed letters of pastoral guidance and instruction on various subjects, and a range of works for use in the monastic classroom, including English 'textbooks' on Latin grammar and

science.

Almost all Ælfric's writing is educational or pastoral in purpose, and he was a teacher to his fingertips, constantly engaged with the question of how best to communicate complex and challenging ideas to his audiences. He was a fluent writer of English prose, and later in his career he developed a beautifully measured blend of prose and alliterative verse which falls melodiously on the ear. His

Life of St Edmund is a nice example of that style; I'm also fond of his poetic

Christmas homily, and there are lots more in the

archives. He was a popular as well as a prolific writer, and his works were still being read and reused as late as the thirteenth century - he had provided an invaluable resource for others to draw on, and while political upheavals in the centuries after his death altered other aspects of Anglo-Saxon literature and culture, the pastoral work of the church for which Ælfric had laboured still went steadily on.

Ælfric was educated at Winchester, under the influential reforming bishop St Æthelwold, and then spent nearly twenty years at Cerne Abbey in Dorset, where he wrote most of his homilies between 987 and 1005. He ended his life as abbot of Eynsham, a village about five miles from Oxford. I recently visited Eynsham for the first time, and this post is really an excuse to share some of my pictures from that visit - there's nothing left of Eynsham Abbey, but it's a lovely village, and it's possible to stand on the site where Ælfric's abbey once stood.

Eynsham was 'Ælfric's abbey' in more ways than one, since it was founded - in a way - for him. He was its first abbot, and it was founded in 1005 by his patron Æthelmær, the head of one of the leading families of Anglo-Saxon England. Æthelmær and his father Æthelweard had supported Ælfric's work for many years, and his collection of

Lives of Saints was written for them (you can read the preface addressed to them

here). They were a powerful and well-connected family, descended from one of the brothers of Alfred the Great, who were proud of their roots in the royal line of the kings of Wessex and were involved in contemporary politics - as ealdorman of the 'western shires', Æthelweard governed part of the south-west (probably Somerset, Devon and Dorset), and was a counsellor to King Æthelred. Both father and son had sophisticated literary and spiritual interests: Æthelweard was the author of a chronicle in Latin - a remarkable achievement for a layman at this date - and the family's patronage of Ælfric must have been a great help and protection to him.

Æthelweard probably died around 998, and a few years later his son Æthelmær founded Eynsham Abbey and installed Ælfric as its abbot. There may have been a monastic community of some kind at Eynsham earlier in the Anglo-Saxon period, but under Ælfric - with his impeccably Benedictine education - it became a Benedictine monastery.

Eynsham lies near the Thames, a little way south of what was once the great forest of Wychwood, and divided from Oxford by the green hills of Wytham Woods, which you can see in the distance here. This view can't have changed much since Ælfric's day:

This is a quiet corner of Oxfordshire now, but when the abbey was founded in 1005 England was in turmoil, under near-constant attack from Viking armies, and riven by internal conflict too. Three years earlier there had been a horrific incident just a few miles away in Oxford, when on

St Brice's Day 1002, in response to an edict from King Æthelred, a group of Danes living in the city were chased into a church (on the site of what is now Christ Church Cathedral) which their pursuers burned down. In 1005, the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also records a 'great famine in England, such that no one ever recalled one so terrible before'. The following year a Viking army burned Wallingford - less than twenty miles away from Eynsham - and flaunted their dominance over Wessex all along the Berkshire Downs (I'll tell you that story another day), finishing up by parading their stolen booty past the very walls of Winchester, Ælfric's former home.

Æthelmær seems to have founded Eynsham around the time he left Æthelred's court for a few years, perhaps escaping the violent factionalism which reigned there in the early 1000s. (He

came out of retirement in 1013, to lead the submission of Wessex to the Danish king Svein Forkbeard.) Eynsham was perhaps a kind of retirement post for Ælfric, too; most of his writings were composed in the 990s, so when he came here his life's work was almost all behind him, and he is thought to have died around five years later.

But Ælfric was anything but unworldly - though he was 'in the world but not of the world' - and medieval abbots were expected to be practical people, so it can't have been entirely a sinecure. There are plenty of reminders of industrious abbots at Eynsham, dating mostly to the centuries after Ælfric: while the first abbot probably never had the chance to do much here, the village is criss-crossed by signs of later monastic fishponds, building programmes, water engineering - all the practical things which leave marks on a landscape over many centuries of daily life.

It's a pretty village of honey stone, quiet and friendly, an oasis between the noisy A40 to the north and to the south the 'warm, green-muffled hills' which separate it from busy Oxford. It feels like another world - a peaceful, pleasant world. When Ælfric came here a thousand years ago, Oxford was already a town (a

burh) but not yet a university city; in him, little Eynsham can claim an older scholarly heritage than its neighbour, the oldest university in England.

If you like going in search of medieval abbeys in England you have to use a fair bit of imagination, because most of the time you'll be looking at ruins - or empty space. For various reasons, in the past few years I've visited several sites of what were once great abbey complexes, and they all have their own stories to tell about the way later centuries have managed to accommodate the traces of their monastic past. I've been to

St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, now an English Heritage site with an entrance fee and guidebooks and the footprint of the abbey carefully marked out;

Crowland, a dream of a Gothic ruin;

Bury St Edmunds, a large and well-kept public park where children play on the graves of the abbots; Abingdon, where the stones of the abbey led by Ælfric's teacher St Æthelwold are rearranged into tasteful Victorian follies; Peterborough, where the town has largely eaten up whatever remained of the monastery; and Reading, where the abbey's former precincts now contain

modern skyscrapers more ghostly in their glittering emptiness than any medieval ruin could be. Most of these towns once revolved around their monasteries, and losing them must have been like having their heart ripped out. But places grow back, and build in different ways upon the ruins.

Eynsham was never on the scale of those great monasteries, but what stands on its site now is more appropriate than any of them. It's a churchyard, of the rambling shadowy rural kind, which lies between the (Anglican) church of St Leonard's on one side and the (Catholic) church of St Peter's on the other. Their two adjoining graveyards cover the space where the abbey church once stood. The site has been well investigated, and a neat little collection of signs point out the exact spot of each of the abbey's buildings; if you exercise a bit of imagination you can see church, cloisters, refectory, rising up out of the ground before you.

This sign on the wall marks the site of the high altar of the Anglo-Saxon church, and it points out that Ælfric - as the first abbot, entitled to a place of honour in death - was probably buried very close by. I hadn't expected that. If this is the site of his now-vanished tomb, it's a beautiful one - surrounded by well-tended graves just a few years old, bright with flowers and tokens of love. On this July day it was like an informal rose garden, with a view of the green hills beyond, still and quiet except for the occasional shriek of a red kite. A resting-place among Eynsham's parishioners seems fitting for this most pastorally-minded of monks - the shepherd amid his flock.

Fitting too that the site should span the grounds of both the Catholic and Anglican churches - however it turned out that should happen, it's a lovely thing. When you stand on the site of a destroyed medieval abbey - and if you are, as I am, fond of medieval monks and their ancient, industrious, imperfect but very human communities - it's hard not to think of the wanton violence which laid waste to them and all that unnecessary loss. But this is something more peaceful and rather beautiful, a belated healing of wounds. (A very recent one; the Catholic church was only built in the 1960s.)

Some remains found during the excavation of the abbey are buried in the Catholic cemetery.

The Anglican church, St Leonard's, was (and is) the parish church for the people of the town, and dates to the thirteenth century. The abbey church in its heyday would have been quite a bit larger.

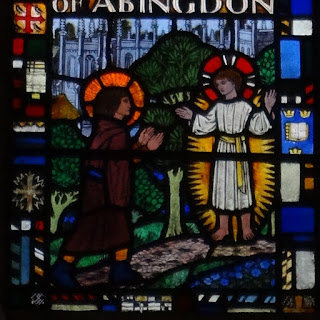

Inside the church, I was pleased to find Ælfric in glass:

The church also displays various bits of stone which are supposed to have come from the abbey buildings when they were destroyed, such as this stranded above the doorway:

And the base of the font, said to have been a capital in the abbey church:

And some fragments of medieval stained glass, reassembled into a kaleidoscope of colour:

The Catholic church, on the other side of the abbey-now-churchyard, is very different, and has an interesting history of its own which you can read about

here.

Though plain on the outside, inside it's elegant in its simplicity, and warmly welcoming.

This church adjoins the site of the abbey buildings, and behind the church is a meadow where the refectory and kitchens used to be:

It's called the Tolkien Meadow, after Tolkien's eldest son, Fr John Tolkien. He was the priest here when the archaeological excavations were going on in the early 1990s, and apparently took an enthusiastic interest in the project to discover more about the abbey. It's wonderful to think of Tolkien's son in Ælfric's abbey - Tolkien (the elder) must have taught Ælfric's work many times, and there's even a brilliant little nod to Ælfric in

The Lord of the Rings...

The meadow contains a limestone boulder which was discovered under the foundations of the abbey when they were excavated. According to the guide, it was in a deep ditch which was dug over 3000 years ago, and 'the archaeologists think that the builders of the abbey decided to incorporate the stone into the wall foundations rather than move it'. It's a solid reminder of the ancientness of this site - Ælfric, living here a thousand years ago, is closer to us than he was to the people who dug the ditch where this stone lay.

And the hills are older still, of course, and he would have seen them.

After inspecting the site of the abbey church, it's possible to walk the perimeter of the medieval abbey - boundaries change slowly in the English countryside, and the modern roads still follow the lines of their medieval predecessors. It's the kind of place where the guide says 'the main road was diverted west in 1217 to expand the abbey precincts', and there the road still is, as if 1217 was really just the other day.

Another set of useful signs trace the path to the south of the village, around the sweep of the abbey's fishponds. This was the grand plan of a thirteenth-century abbot, and the land has hardly been touched since the abbey was destroyed; it's now an extensive green meadow, with weeds and waterfowl, still watery after eight centuries.

I do like a good heritage trail, and this is a very good one - a kind of secular Stations of the Cross, or Rogation procession of the kind

Ælfric preached about. Part of the idea of a Rogationtide procession is that by walking the borders of your community you come to know it better, to feel its shape, and to remember what (and who) falls within its bounds. That has a practical and a spiritual function, at one and the same time. I wonder if Ælfric took a Rogation procession out into the fields the first spring he was at Eynsham, as he got to know the lands and souls entrusted to his care.

There are lots of things to think about here, in an empty meadow on a sunny July day. I was thinking about service. In his Preface to the

Lives of Saints, Ælfric addresses his two noble patrons and summarises for them some of the characteristics of the collection which is to follow:

Ælfric gret eadmodlice Æðelweard ealdorman, and ic secge þe, leof, þæt ic hæbbe nu gegaderod on þyssere bec þæra halgena þrowunga, þe me onhagode on Englisc to awendene, for þan þe ðu, leof swiðost, and Æðelmær swylcera gewrita me bædon, and of handum gelæhton eowerne geleafan to getrymmenne mid þære gerecednysse, þe ge on eowrum gereorde næfdon ær...

We writað fela wundra on þissere bec, for þan þe God is wundorlic on his halgum, swa swa we ær sædon, and his halgena wundra wurðiað hine, for þan þe he worhte þa wundra þurh hi. An woruldcynincg hæfð fela þegna and mislice wicneras; he ne mæg beon wurðful cynincg buton he hæbbe þa geþincðe þe him gebyriað, and swylce þeningmen þe þeawfæstnysse him gebeodon. Swa is eac þam ælmihtigan Gode þe ealle þincg gesceop: him gerisð þæt he hæbbe halige þenas, þe his willan gefyllað, and þæra is fela on mannum anum, þe he of middanearde geceas, þæt nan bocere ne mæg, þeah þe mycel cunne, heora naman awriten, for þan þe hit nat nan man. Hi synd ungeryme swa swa hit gerisð Gode; ac we woldon gesettan be sumum þas boc mannum to getrymminge and to munde us sylfum, þæt hi us þingion to þam ælmihtigan Gode swa swa we on worulde heora wundra cyðað.

[Ælfric humbly greets ealdorman Æthelweard, and I say to you, my beloved man, that I have now gathered in this book the Passions of the saints which it was appropriate for me to translate into English, because you, my dearest man, and Æthelmær asked me for such writings, and received them from my hands in order to strengthen your faith by means of these stories, which you never had in your own language before...

We will write about many wonders in this book, because God is wonderful in his saints, as we said before; and the wonders of his saints bring honour to him, because he worked those wonders through them. An earthly king has many thegns and various officers; he cannot be an honourable king unless he has the things which are fitting to him, and such attendants to offer him their obedience. So it is also with Almighty God who created all things: it is fitting for him that he have holy thegns, who carry out his will, and of these there are many among mankind, whom he chose out of the world, so that no learned person – even if he knows many things – can write down their names, because no one knows them. They are beyond number, as is fitting for God. But we wanted to compile this book about some of them, for the encouragement of people and as security for ourselves, so that they could intercede for us with Almighty God, just as we make their wonders known in the world.]

The metaphor of the saints as God's 'thegns' is obviously one chosen to suit Ælfric's audience: Æthelweard and Æthelmær knew very well that 'an earthly king has many thegns and various officers', since they had fulfilled such a role themselves. The king's court was as apt a metaphor for them as it was for Alfred the Great when he used it

in a text all three may have been familiar with, talking about how everyone at the king's court - from the highest to the lowest, from the royal chamber to the jail-cell - is in some sense in the presence of the king, just as everyone in the world is to some degree in the presence of divine wisdom, though some may be closer and others further away. There is a suggestion of that diversity here too in the reference to the

mislice 'diverse, various' kinds of servants who serve God, and it's a theme Ælfric develops at greater length in his

sermon for All Saints' Day - there are many different kinds of saints, who by their different lives and deaths bring glory to God.

This doesn't only apply to saints, of course. One of the most attractive themes which crops up in several places in Old English poetry is the 'gifts of men', celebrating all the many and various skills which different people contribute to society. When Ælfric addresses this theme he does so in an explicitly Biblical context, in his

homily for Whitsun, where he describes the gifts of the Holy Spirit:

He sylð his gife ðam ðe he wile. Sumum men he forgifð wisdom and spræce, sumum god ingehyd, sumum micelne geleafan, sumum mihte to gehælenne untruman, sumum witegunge, sumum toscead godra gasta and yfelra; sumum he forgifð mislice gereord, sumum gereccednysse mislicra spræca. Ealle ðas ðing deð se Halga Gast, todælende æghwilcum be ðam ðe him gewyrð; forðam ðe he is Ælmihtig Wyrhta, and swa hraðe swa he þæs mannes mod onliht, he hit awent fram yfele to gode.

[He gives his gifts to whomever he will. To some men he gives wisdom and eloquence, to some good knowledge, to some great faith, to some the power to heal the sick, to some the power of prophecy, to some the power to distinguish between good and evil spirits; to some he gives various languages, to some interpretation of various sayings. The Holy Ghost does all these things, distributing to everyone as seems good to him; for he is the Almighty Maker, and as soon as he enlightens the mind of a man, he turns it from evil to good.]

But other Anglo-Saxon writers elaborated on the theme with a wider range of very practical skills, including climbing trees, sailing ships, architecture, swimming, looking after horses, hunting and hawking, and much more. Here's an example from the poem

Christ II:

Sumum wordlaþe wise sendeð

on his modes gemynd þurh his muþes gæst,

æðele ondgiet. Se mæg eal fela

singan ond secgan þam bið snyttru cræft

bifolen on ferðe. Sum mæg fingrum wel

hlude fore hæleþum hearpan stirgan,

gleobeam gretan. Sum mæg godcunde

reccan ryhte æ. Sum mæg ryne tungla

secgan, side gesceaft. Sum mæg searolice

wordcwide writan. Sumum wiges sped

giefeð æt guþe, þonne gargetrum

ofer scildhreadan sceotend sendað,

flacor flangeweorc. Sum mæg fromlice

ofer sealtne sæ sundwudu drifan,

hreran holmþræce. Sum mæg heanne beam

stælgne gestigan. Sum mæg styled sweord,

wæpen gewyrcan. Sum con wonga bigong,

wegas widgielle. Swa se waldend us,

godbearn on grundum, his giefe bryttað.

To one he sends wise speech

into his mind’s thoughts through the breath of his mouth,

fine perception. One whose spirit is given

the power of wisdom can sing and speak

of many things. One can play the harp well

with his hands loudly among men,

strike the instrument of joy. One can tell

of the true divine law. One can speak of the course of the stars,

the vast creation. One can skilfully

write with words. To one is granted success in battle,

when archers send quivering arrows flying

over the shield-walls. One can boldly

drive the ship over the salt sea,

stir the thrashing ocean. One can climb

the tall upright tree. One can wield a weapon,

the hardened sword. One knows the expanse of earth’s plains,

far-flung ways. Thus the Ruler,

God's Son on earth, gives to us his gifts.

I love these catalogues of skills. They are celebratory and generous, finding something to praise in gifts of many different kinds, and valuing them all. All require skill and labour, all are important to society, all have a beauty of their own. In this context it's an explicitly Christian viewpoint, but a distinctively Anglo-Saxon one too - fitting for a culture for whom

Weland the Smith was a hero. I can't really imagine what a modern version of this poem would look like ('One can phrase snarky Tweets so they fit within 140 characters...'); we just don't value craft in the same way, and our hierarchy of skills is quite a bit more rigid.

Within this view of the world, all gifts can be not only valuable in themselves, but a service to others and to God. Eynsham made me think of that. Æthelweard and Æthelmær had practical gifts of their own ('wise speech', they must have hoped, whether Æthelred listened to them or not) and they nurtured Ælfric's gifts as a writer and teacher, and Ælfric in his turn spent his life sharing those gifts with the world. Think of all the skills, too, which built and maintained an abbey like Eynsham - the labourers and craftsmen, the abbot with his fishponds, the cooks in the kitchen which is now Tolkien Meadow. Building and running a community takes so much dedicated labour - just read

this touching history of Eynsham's Catholic church and see all the years of work which went into getting that church built, and all the very different but clearly much-loved parish priests whose diverse gifts are affectionately remembered by their parishioners. Such work is rarely celebrated and is often lost to history, because it's not dramatic or self-aggrandising - it's incremental, collaborative, self-giving, and it does an unfathomable amount of good.