St Edmund (Chichester Cathedral)

16 November is the feast of St Edmund of Abingdon, Oxford scholar and Archbishop of Canterbury, who died in 1240. (It's also the feast of St Margaret of Scotland and one of the feasts of St Ælfheah, a predecessor of Edmund's at Canterbury two centuries earlier.) St Edmund had a long and somewhat turbulent career, as many medieval bishops did, and we have a mass of detailed information about his life - the cause of his canonisation was started very shortly after his death, which means that materials to support the cause were gathered from his contemporaries and those who had known him well.

For me (quite selfishly), the interest of the hagiographical material about St Edmund lies in his early life, as a child in Abingdon and then a young scholar in late twelfth-century Oxford. It gives a vivid picture of Oxford in the early days of the university, which is not dissimilar, in some essential ways, from the work of universities and schools today. Education was one of the glories of the medieval church, and it's a shame that so many people today believe (on the basis of unthinking assumption, rather than fact) that the church in the Middle Ages was somehow 'anti-education'; nothing could be further from the truth, as St Edmund's life and story (and those of many others like him) demonstrate.

It’s also rare to know so much about the early life of a medieval figure, or to have such specific details about their childhood that it becomes possible to visit and envision the scenes of their youthful experiences. In this post I thought I'd share some of those early stories about Edmund, and take you on a visit to Abingdon, where they still cherish the memory of their home-grown saint.

All quotations are taken from the thirteenth-century The Life of St Edmund by Matthew Paris, ed. and trans. C. H. Lawrence (Stroud, 1996).

St Nicholas' church, Abingdon

Abingdon is a market town on the River Thames, six miles south of Oxford, and (like the village of Eynsham, north of the city) it has a much longer history - and longer scholarly history - than its more famous university neighbour. Abingdon actually claims to be 'the oldest town in Britain', because there's evidence of settled inhabitation here in the Iron Age; it subsequently became a Roman town, and in the Anglo-Saxon period it was the site of an important monastery. One of the most dynamic and influential figures in the late Anglo-Saxon church, St Æthelwold - he of the splendid Benedictional, and a champion of monastic reform and education - was abbot of Abingdon before he became Bishop of Winchester, and the town still bears traces of the work he did here in the tenth century. (The abbey millstream still follows the course he set for it, a thousand years later.)

Abingdon from above, looking south-east (from the roof of the town museum)

In Edmund's day the abbey would have been an imposing presence in the town, physically, institutionally, and psychologically. It was a major landowner here and for miles around, as well as the chief provider of education and healthcare. St Edmund was born in Abingdon around 1174, probably into a fairly prosperous middle-class family in trade. His parents were named Reginald and Mabel, and Edmund seems to have been the eldest of a large family; he had at least three brothers and two sisters, whom he took responsibility for after his parents’ death. Edmund's name might perhaps suggest that he was born or baptised on the feast of St Edmund of East Anglia (20 November); in the last days of his life he made reference to his namesake, telling his companions that after his death he would return to them on the feast of St Edmund, king and martyr, so perhaps he saw a link between himself and the Anglo-Saxon saint.

Abingdon from the river

Records show that Edmund's father owned several properties in Abingdon, and the family home was in West Street (now West St Helen Street). The house was remembered as Edmund's birthplace, and a chapel was established nearby at the end of the thirteenth century in memory of the saint. The street-name St Edmund's Lane preserves the name:

These were relatively modest origins, and it was entirely through Edmund's parents' commitment to his education, and his own hard work, that he later achieved a position of eminence. It was Edmund’s mother Mabel who was the guiding and inspiring influence of his early life, especially his education. His father died when Edmund was young, and Mabel encouraged her sons’ education, supporting them first at Oxford and then at Paris. She was a particularly devout and determined woman, known for her works of fasting, almsgiving and prayer; ‘of all the widows of Abingdon she was said to have been the jewel’, Matthew Paris says.

Abingdon has two medieval churches in addition to the lost abbey church, and one of them, St Nicholas', is associated with Mabel; at least, she was buried there. St Nicholas' stood at the edge of the abbey grounds, and though the abbey and its big church are gone, the little church of St Nicholas remains. This is what it looked like on St Edmund's day two years ago:

The church was founded in 1170, so it was brand-new in Edmund's childhood and not very old when Mabel was buried there. It has a plaque to Edmund and his mother:

A view of the inside:

Attached to the church is a gateway which would once have led into the abbey's grounds:

There's something evocative about a doorway which still stands and gapes, but no longer leads to the place it was built for.

This gateway is from the fifteenth century, and has a statue of the Virgin Mary above the door:

St Æthelwold and his fellow abbots were running a school at Abingdon when Oxford was just an ordinary Anglo-Saxon town, a ford over the Thames, but by Edmund's youth in the late twelfth century Oxford was increasingly gathering the communities of teachers, scholars and students who would in time form the nucleus of the university. Reginald and Mabel sent their son to be educated in a grammar school in Oxford, and the first signs of his future sanctity were said to have manifested themselves when he was around twelve years old. He was a devout child, and at that age he decided to pledge himself in a sacred marriage to the Virgin Mary. He placed a ring on the finger of a statue of the Virgin in token of his vow, and after making his promise he tried to remove the ring - but by miraculous power it could not be removed. (This miracle was supposed to have taken place in the church of St Mary the Virgin, in Oxford.)

Another miracle in Edmund's childhood took place when he went out one midsummer day for a walk with some fellow students in the meadows near Oxford (traditionally said to be the river meadows near what is now Magdalen College). He wandered away from his companions,

And, lo, he came upon a bush marvellously covered with most beautiful flowers, contrary to its habit and out of its proper season, scattering its fragrance far and wide all around. As he pondered on this, it occurred to him that it had some heavenly meaning, and kneeling down, he prayed, saying 'O God, who didst appear to the holy Moses on Mount Sinai in the figure of a burning bush that was not consumed, reveal to me what is portended by this miraculous thing.'

As he sank down on his knees, alone, praying tearfully, a flood of light from heaven shone round him, and in it, to his stupefaction, there appeared the infant Christ shining with great clarity, who spoke to him words of consolation: 'I am Jesus Christ, the son of Blessed Mary the Virgin, your spouse, whom you wedded with a ring and took as your Lady. I know the secrets of your heart, and I have been your inseparable companion as you walked alone. From now on I promise you that I and my mother, your spouse, shall be your helpers and comforters.' Saying this, he imprinted a blessing on the young man's brow with these words: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, and added 'Sign yourself often thus and repeat this in memory of me.'

He remained long in that place, praying on his knees and asking the Holy Spirit to grant him the learning that conduces to salvation with the other virtues.

The spire of St Helen's church, Abingdon, from the meadows outside the town

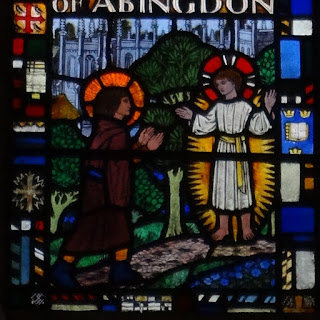

This window in the church of St Edmund and St Frideswide, Oxford, shows Edmund's vision:

The scene at the bottom is his vision of the Christ-child, with towers which evoke Oxford's spires behind him:

As he grew older Edmund continued his education at Oxford and then at Paris, before coming back to Oxford to teach. He remained a serious and devout young man, and his hagiographer observes that ‘when as a youngster of more mature years he was put to the study of liberal arts, he proceeded of his own will along the road by which he had previously been led, being – as his name signified – blessed and pure’. (The Old English name-element ead- means ‘blessed’.) He engaged in strict ascetic practices to mortify his flesh, following the example to which his mother had encouraged him; when he was studying in Paris she sent him clothes (as mothers do!) along with a hair-shirt, urging him to wear it as a form of self-discipline. But despite this he remained, his companions recalled, ‘affable and kind to others’, ‘full of joy and gaiety’, and ‘a refuge of the oppressed, a consoler of the wretched and a most kind comforter of the afflicted’.

When he became a Master of Arts and began lecturing at Oxford, he was known for going to hear mass daily before giving his lectures, ‘which was more often than customary among lecturers at that time’, comments Matthew Paris (or indeed any time, I suspect...). While he was still what we’d now call an Early Career Researcher, Edmund gave financial help to support poor scholars at the university (sometimes selling his own books in order to do so) and built a chapel in Oxford dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. The miracles of this phase of Edmund’s life are closely tied to his work as a lecturer: stories tell how he contended with the devil while making lecture notes for his students; how he healed one of his scholars from a serious illness; how he miraculously kept rainclouds away when he was preaching outside, and so on. He wrote, lectured and preached with great skill and eloquence; ‘when he lectured or preached, it seemed to his hearers that the finger of God was writing in his heart the words of life that flowed from his mouth like the river of paradise.’ He had so little concern for wealth that one of his colleagues testified that ‘when he received money from his scholars, he was in the habit of placing it, or rather tossing it, in the window, as if it were available to everybody’, and people would carry it away!

By this time his mother had died, but she was still exerting a powerful influence on his life. At this point he was lecturing on the liberal arts, but had not yet progressed to teaching theology; and then he had a vision of his mother which sent him in a new direction:

[At a time when he was giving lectures on geometry to his students] his most pious mother, who had died shortly before, appeared to him in a dream, and said: ‘My son, what are those shapes to which you are giving such earnest attention?’ When he replied, 'These are the subject of my lecture,' and showed her the diagrams which are commonly used in that faculty, she promptly seized his right hand and painted three circles in it, and in the circles she wrote these three names: 'Father. Son. Holy Spirit.' This done, she said, 'My dearest son, henceforth direct your attention to these figures and to no others.'

Instructed by this dream as if by a revelation, he immediately transferred to the study of theology.

This is a lovely story – a spur of parental guidance (disapproval?) from beyond the grave! The fact that she draws circles on his hand, as a mother might with a child, is a nice touch, echoing the sign Christ drew on Edmund's forehead in his earlier vision. Mabel is not imagined here disapproving of geometry per se; the point is that this is basic knowledge, and it’s now time for Edmund to progress to higher and deeper subjects, through the study of theology. This story suggests something of the powerful bond between Edmund and his mother, enduring after her death; but it’s also relevant that in the Middle Ages educational subjects – from Boethius’ Lady Philosophy to Geometry and Theology, as in the image below – are often represented as female. Here the real woman Mabel is envisaged teaching her son as if she were a vision of Theology itself, guiding the promising student towards the Queen of the Sciences.

A female figure teaching Geometry (BL Burney 275, f. 293)

Edmund's best-known work in the Middle Ages was his Speculum Ecclesie, which was probably written during this period of his career. It's a work on the contemplative life, offering (among other things) meditations on different moments in the life of Christ, aiming to help the reader to enter imaginatively into the scenes of his Passion and feel intense compassion for his sufferings. I don't know whether people read the Speculum Ecclesie today, but most students of Middle English will have read a poem which survives as part of it. This is one of the earliest, shortest, and most popular devotional poems in Middle English:

Nou goth sonne under wod,

Me reweth, Marie, thi faire rode.

Nou goth sonne under tre,

Me reweth, Marie, thi sone and thee.

[Now goes the sun under the wood,

I grieve, Mary, for your fair face;

Now goes the sun under the tree,

I grieve, Mary, for thy son and thee.]

This short poem is designed to be a spur to meditation on the Crucifixion, perhaps at the appropriate hour of the day when the sun begins to set. Apparently very simple, the poem is dense with meaningful wordplay: as the sun sets behind the wood, so Christ the Son is shrouded in darkness on the wood of the cross, the tree; that is, the 'rode', which means both 'face', and 'rood' (cross). And here we have another pair of a mother and her son, and their strong emotional bond: the poem encourages the reader to meditate and dwell on Christ's crucifixion by approaching the Son through the Mother, to feel compassion for his suffering as it is reflected in her grief (underlined by that wordplay on 'rode' - his cross and her face). We don't know who wrote this precious little poem, but it's possible it was St Edmund himself - and either way, how wonderful it is that this poem should be associated with a saint whose mother was such an important presence in his life.

In 1222 Edmund became treasurer of Salisbury Cathedral, and began increasingly to preach outside Oxford; in 1233 he was selected (as fourth choice) to be the next Archbishop of Canterbury. His time as archbishop involved mediating in various political crises and disputes between Henry III and his barons, as well as conflict between Edmund and the monks of Canterbury; but it lasted only seven years. In 1240, on his way to Rome for a council with the Pope, he was taken ill on the journey. He died, and was buried at Pontigny - a long way from Abingdon and the banks of the Thames.

On his deathbed he was happy and peaceful, and made play with a proverb which the hagiographer quotes in English:

After being fortified by the viaticum of salvation, he began to seem a little better, and became merry, as though he had been fed to repletion by the celestial banquet. Supported by a pillow so that he could sit, he looked serene and he joked with those standing around, telling them this proverb in English: ‘Men seth gamen goth on wombe. Ac ich segge, gamen goth on herte’; which is to say, play enters the belly, but now I say play enters the heart. The meaning of this epigram is: it is commonly said that a fully belly makes men joyful and ready for play; but it is my opinion that a heart fed by a spiritual feast produces a serene conscience, freedom from anxiety and joyfulness. In fact, he displayed such joyfulness and hilarity that those who were with him were quite astonished.

Edmund's name is preserved in Oxford in the college St Edmund Hall, in the east of the city, which stands on the site of a house where Edmund is said to have taught. There's a modern sculpture of Edmund in the grounds of the college (above), which shows him reading - a companion to today's students, who can sit and read next to him if they like. He is depicted in thirteenth-century stained glass, made within a few decades of his death, in the church of St Michael at the Northgate:

Back in Abingdon, the Catholic church (a Victorian building) is dedicated to him and to the Virgin Mary, the mother and bride who was so constant a presence in his spiritual life:

And to close, here are a few more pictures of Abingdon, because I'm very fond of it. A lively small town, full of civic pride and rich in history, is just about my favourite kind of community; it's not very fashionable to love such places, but I do. Abingdon has an excellent town museum, in this gorgeous building in the centre of the town:

From the roof you can look across the town, down to the Thames and beyond to Didcot Power Station...

The clump of trees in the last picture are growing on the site of Abingdon Abbey, which still takes up a large expanse of ground in the east of the town. Much of the site is now a public park (well, a bit of it's under Waitrose carpark).

Standing here in the Middle Ages, you would have been looking at the west end of a huge church - apparently along the lines of the west front at Wells Cathedral. Can you imagine it?

This would all have been where the abbey church once stood:

The park has some picturesque ruins which look like they're the remains of the abbey, but are in fact mostly Victorian follies (in some cases with medieval stone):

Lots of empty and evocative doors to nowhere here.

But there are some remaining buildings from the abbey, too - this is the impressive 'Long Gallery' (perhaps built as a guesthouse for the abbey), dating to the fifteenth century:

Look at those beams!

And underneath are some impressive vaults:

If that's just the guesthouse, what might the church have been like...

I was in Abingdon most recently on August Bank Holiday this summer; the park was full of children and their parents, playing on the site of the abbey church, and the flowerbeds were bright with colour. I don't know what St Æthelwold would have thought of it all, but it brought Edmund and Mabel to mind.