This is the church of St Dunstan, Canterbury, a medieval church which has an interesting history stretching over nearly a thousand years, but is most famous for being the (probable) burial-place of the head of St Thomas More. I went to visit it a few weeks ago, since I'd never been before and I'm particularly interested in St Dunstan this year.

I'll start at the beginning, with Anglo-Saxon Canterbury, but feel free to skip right over that and get straight to Thomas More... But first a few pictures of the church:

This is the east window:

This is the east window:

And I liked this window too:

St Dunstan's is in the area of Canterbury outside the city walls, on the main road leading from the west - the direction from which Chaucer's pilgrims would have approached the city, if they had ever got that far. (The last place on the route mentioned in the Canterbury Tales is the village of Harbledown, the nearest settlement to Canterbury from the west). This area grew up to cater for pilgrims who hadn't reached the city before the gates closed for the night, and still today has some picturesque hostelries which are medieval in origin.

The church was probably founded in the late tenth century, perhaps during Dunstan's lifetime, but it only acquired its dedication to St Dunstan some time in the eleventh century. The first post-Conquest archbishop, Lanfranc (1070-1089), gave the church to the priory of St Gregory, which he had founded in Canterbury (much to the annoyance of the existing religious foundations in the city, especially St Augustine's Abbey, as I've mentioned before). St Gregory's was founded in 1084; as far as I can discover, the earliest evidence for this church's dedication to St Dunstan comes at that point, and so while the church history speculates the dedication was changed after Dunstan's canonisation in 1029/30, I'd wonder if it was rather a product of the 1080s. I've discussed before how immediately after the Norman Conquest Anglo-Saxon traditions were apparently discarded at Canterbury (guardian angels and devotion to the Immaculate Conception among them), and Lanfranc had to be taught to believe in the sanctity of St Alphege by Anselm; Dunstan was a casualty of this too, and his feast was dropped from the Canterbury calendar. (I tried to think of a modern equivalent to indicate how shocking this would have been for the Canterbury monks, and an obvious one suggests itself: it would be like the church hierarchy today deciding the English church shouldn't celebrate Thomas More). However, over the next decade Lanfranc - though still 'somewhat raw as an Englishman', as Eadmer tactfully put it - began to look a little more favourably on the traditions of the place he had found himself in charge of. By the 1080s he had apparently been persuaded of the importance of St Dunstan, too, and this was probably the impetus behind the writing of two accounts of Dunstan's life by the monks Osbern and Eadmer, which I quoted from extensively in my past posts.

So the 1080s was the period when Dunstan's memory was beginning to be respected again, and this church's dedication might perhaps be a symptom of that. If so, it would be only the first example of a theme which has run through the history of this church. Apart from its foundation, the most famous event in St Dunstan's medieval history occurred in 1174, when Henry II came to Canterbury to do penance for the death of Thomas Becket. He stopped at St Dunstan's to don sackcloth, and then walked barefoot into the city to St Thomas' tomb. But it's another St Thomas, martyred statesman and victim of another King Henry, who has the place of honour at St Dunstan's. Thomas More's daughter Margaret was married to William Roper, whose family lived in the parish of St Dunstan's. In the late fourteenth century an ancestor of William Roper's had founded a chantry chapel in the parish church, and the Roper family vault was located below it:

The chapel, which is dedicated to St Nicholas, occupies the south-east corner of the church, and looking from the outside you can see how it stands out from the rest of the building - it's on the left of this picture and is built of brick, unusually for the time:

William and Margaret Roper are both buried here, and tradition says that after her father's execution, Margaret rescued the head which had been displayed on a pike on London Bridge, and had it buried in the Roper vault. The entrance to the family vault is on the left here, crowned with a wreath:

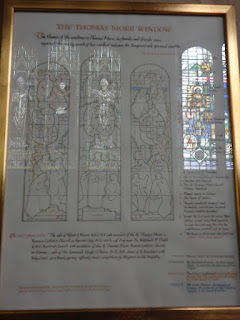

The chapel has three wonderful stained-glass windows, one depicting elements from the life of St Thomas More. I love windows which have lots of detail, so let's go through it bit by bit:

Close-up of the whole thing - isn't it lovely?:

In the centre is St Thomas More himself, with his wife Alice (on his right) and daughter Margaret (seated at his left) and William Roper standing behind:

Another daughter, Cecily, in yellow here:

The male figure here is not Henry VIII, as I first thought (though that would have been fairly inappropriate!) - it's Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and the kneeling woman is Queen Catherine.

This depicts some of Thomas More's contemporaries - St John Fisher (in red), Oxford scholar William Grocyn (seated), Erasmus, and John Colet:

I'm afraid I chose capturing the beautiful red light cast by Fisher's robes over including Colet's head in this picture (sorry, Colet!), but here it is, together with the arms of London, Westminster and the Tudor family, and the symbol of St Dunstan (the ciborium). The little church is one dedicated to St Thomas More in Vienna:

The centre of the window depicts the Agnus Dei, and written across it More's famous words: 'The King's good servant, but God's first'.

On the other side, the arms of Oxford University, the city of Canterbury, the Borough of Chelsea, and the Great Seal of Henry VIII:

The top three scenes depict different aspects of More's life: first More the scholar (seated, reading), with Cardinal Wolsey, and a depiction of his house in Chelsea behind him:

Then More serving at Mass:

And More the martyr:

The figure kneeling on the right here is Thomas Cromwell, and in the background is the Tower of London, where More was executed. Notice how the River Thames runs right across the window from Chelsea to Tower Hill; that's a nice touch.

The figure kneeling on the right here is Thomas Cromwell, and in the background is the Tower of London, where More was executed. Notice how the River Thames runs right across the window from Chelsea to Tower Hill; that's a nice touch.This is only one of three windows in the Roper chapel - here's the second, the most modern:

Among other things, it depicts the visit of Pope John Paul II to Canterbury in 1982, when he and Archbishop Robert Runcie knelt together at St Thomas Becket's shrine (and look, a Canterbury cross!):

The other window is one for the 'medieval people in modern stained glass' files, because it depicts Thomas More flanked by Dunstan and Lanfranc:

Dunstan:

Dunstan:

Lanfranc:

And Thomas More between them, getting all the best colours:

The red and blue is really lovely; in the right light, this would be stunning.

The Roper chapel has a number of framed articles around the walls, which is very nice for those of us who like to know the history of things - but also has the incidental advantage of providing various glassy mirrors in which the windows are reflected. Look:

'Why are all reflections lovelier than what we call the reality?--not so grand or so strong, it may be, but always lovelier? Fair as is the gliding sloop on the shining sea, the wavering, trembling, unresting sail below is fairer still. Yea, the reflecting ocean itself, reflected in the mirror, has a wondrousness about its waters that somewhat vanishes when I turn towards itself. All mirrors are magic mirrors...'

'Why are all reflections lovelier than what we call the reality?--not so grand or so strong, it may be, but always lovelier? Fair as is the gliding sloop on the shining sea, the wavering, trembling, unresting sail below is fairer still. Yea, the reflecting ocean itself, reflected in the mirror, has a wondrousness about its waters that somewhat vanishes when I turn towards itself. All mirrors are magic mirrors...'

Or: 'As in many mirrors we are so many other selves, so are we spiritually multiplied when we meet ourselves more sweetly, and live again in other persons.'

And this is St Thomas More, mirroring Christ.

And this is St Thomas More, mirroring Christ.

3 comments:

A lovely post, thank you. I too am familiar with this beautiful and historic church, much too frequently overlooked by visitors to Canterbury.

If you would permit me to make a small correction, though; Thomas More was never a priest; in the window he is not the priest but the server at Mass. That was a role he frequently exercised.

Thank you for the comment and the correction - looking again at the church guide, I see I misunderstood its description of the scene. I'll change it in the post.

A most interesting blog of a church I know well but not as well as I thought!

Post a Comment