I'm sorry to break this to you, but it's now officially winter. At least, it is according to the Old English calendar poem The Menologium, which calls 7 November 'winter's day' - the first day of winter:

And þy ylcan dæge ealra we healdað

sancta symbel þara þe sið oððe ær

worhtan in worulde willan drihtnes.

Syþþan wintres dæg wide gangeð

on syx nihtum, sigelbeortne genimð

hærfest mid herige hrimes and snawes,

forste gefeterad, be frean hæse,

þæt us wunian ne moton wangas grene,

foldan frætuwe.

And on the same day [November 1] we keep

the feast of All Saints, of those who recently or long ago

worked in the world the will of the Lord.

After that comes Winter’s Day, far and wide,

after six nights, and seizes sun-bright autumn

with its army of ice and snow,

fettered with frost by the Lord's command,

so that the green fields may no longer stay with us,

the ornaments of the earth.

The phrase 'Winter's Day' doesn't occur elsewhere with this precise meaning, but November 7 is dated as the first day of winter by the best Anglo-Saxon authorities on the calendar: Bede in his De Temporum Ratione and Byrhtferth in his Enchiridion. According to their reckoning winter has 92 days and runs from 7 November to 6 February, which means that midwinter falls around the time of the solstice - as you would expect, the turn of the year occurs at the midpoint of the season. (In recent years it has become popular to say that winter begins on the winter solstice; Bede would not be impressed...) There are of course lots of ways of dating such changes, and early medieval practice varied; but Bede took his dating from Roman authorities and explored its theological significance, and in this, as in many other matters, his opinion was very influential. As a result, many later Anglo-Saxon calendars mark the beginning of spring, summer, autumn and winter on 7 February, 9 May, 7 August and 7 November. These are cross-quarter days, which fall halfway between the solstices and equinoxes.

In its description of 'Winter's Day' the Menologium is following in this learned, scientific tradition, but it's also drawing on a conventional topos of Old English poetry: the threat of winter. This is a poem which finds beauty in almost everything about the turning year; in its formulaic phrases, every month is ‘ornamented’ or ‘adorned’ or ‘distinguished’ by the features and feasts it contains, and in past posts on this poem we’ve seen the exuberance of spring, the brightness of summer, the plenty of autumn. But there’s no such lingering on the beauty of winter; all the beauty belongs to what's lost when winter takes hold. We have a last glimpse of the loveliness of the abundant harvest, sigelbeortne hærfest, 'sun-bright autumn'. Then winter seizes it (the verb is a violent one, genimð ‘plucks, snatches’) with its army of frost and snow, and captures the earth for another year. Winter comes in like an invading warrior and puts autumn in chains, and the green fields which decorate the earth are permitted to stay with us no longer. There's a melancholy contrast between the two similar-sounding words frætuwe and gefeterad – between the green summer fields adorned (‘fretted’) with beauty, and the winter fetters of frost.

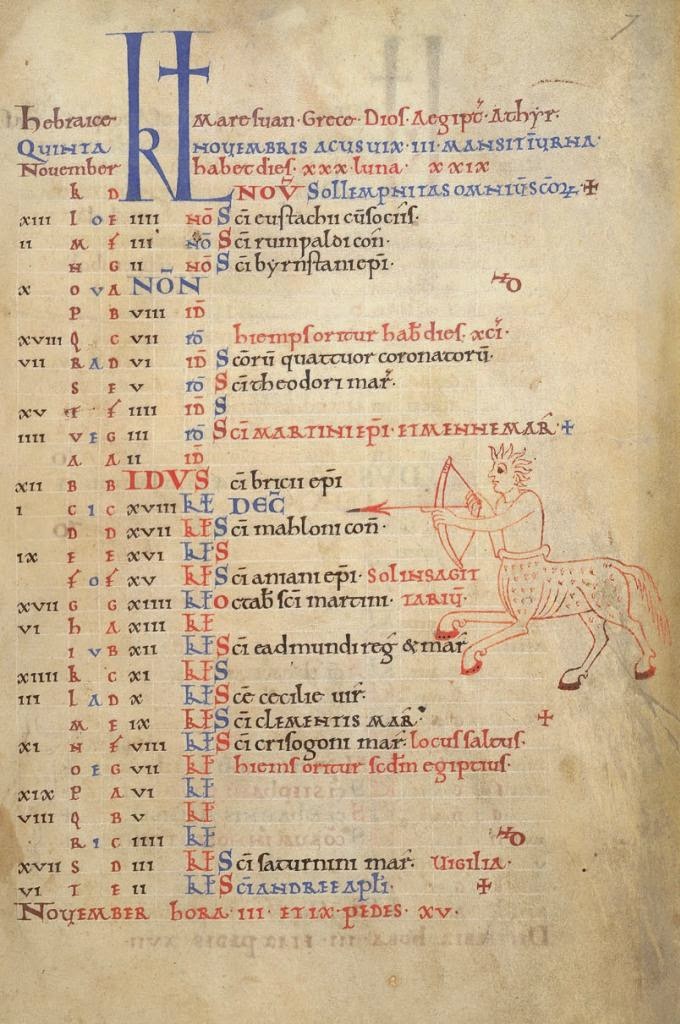

11th-century calendar from Christ Church, Canterbury (BL Arundel 155, f.7)

with the beginning of winter marked on 7 November

This idea of winter imprisoning and chaining the earth will be familiar to anyone who's read a little Old English poetry. There are many, many examples of winter as danger and sorrow: The Seafarer lamenting his cold feet and his burning heart as he sails on the icy ocean, the speaker in The Wife's Lament imagining her lover alone and grieving beneath a storm-dashed cliff, Weland in chains in Deor suffering 'wintercealde wræce', 'winter-cold exile'. But perhaps the most famous - and my favourite - instance is The Wanderer, in which an exile, mourning the loss of home, lord and friends, is trapped in a winter which is his own grief:

Oft ic sceolde ana uhtna gehwylce

mine ceare cwiþan. Nis nu cwicra nan

þe ic him modsefan minne durre

sweotule asecgan. Ic to soþe wat

þæt biþ in eorle indryhten þeaw,

þæt he his ferðlocan fæste binde,

healde his hordcofan, hycge swa he wille.

Ne mæg werig mod wyrde wiðstondan,

ne se hreo hyge helpe gefremman.

Forðon domgeorne dreorigne oft

in hyra breostcofan bindað fæste;

swa ic modsefan minne sceolde,

oft earmcearig, eðle bidæled,

freomægum feor, feterum sælan,

siþþan geara iu goldwine minne

hrusan heolstre biwrah, ond ic hean þonan

wod wintercearig ofer waþema gebind...

Wat se þe cunnað, hu sliþen bið sorg to geferan,

þam þe him lyt hafað leofra geholena.

Warað hine wræclast, nales wunden gold,

ferðloca freorig, nalæs foldan blæd...

Often I must alone, every day before dawn,

lament my sorrow. There is now none living

to whom I dare openly speak

the thoughts of my mind. I truly know

that it is a noble virtue among warriors

for a man to bind his spirit-chest fast,

conceal his heart, whatever he may think.

The weary mind cannot withstand fate,

nor the troubled heart provide help.

And so those eager for glory often

bind fast sorrowful thoughts in their breasts;

so I have had to keep my mind –

often wretched, deprived of homeland,

far from kinsmen – fastened in fetters,

since long ago I buried my lord

in the darkness of the earth, and I from there

journeyed, winter-sorrowful, over the binding waves...

He who has experienced it knows

how cruel sorrow is as a companion

for him who has few beloved friends.

The path of exile holds him, not twisted gold;

a frozen spirit, not the glory of the earth.

In this poem winter infects you, it gets into your heart: the speaker describes himself as wintercearig, 'winter-sorrowful', perhaps 'as desolate as winter', and he has a 'frozen spirit', ferðloca freorig. This is a painful, claustrophobic kind of enclosure; the earth is trapped beneath its winter covering like the aching heart concealed in the grieving warrior’s breast, which strains at its enforced silence. But this is not only a personal but a universal sorrow, the fate of all human society, as if the future of the world could be summed up in one phrase: winter's coming.

Ongietan sceal gleaw hæle hu gæstlic bið,

þonne ealre þisse worulde wela weste stondeð,

swa nu missenlice geond þisne middangeard

winde biwaune weallas stondaþ,

hrime bihrorene, hryðge þa ederas.

Eorlas fornoman asca þryþe,

wæpen wælgifru, wyrd seo mære,

ond þas stanhleoþu stormas cnyssað,

hrið hreosende hrusan bindeð,

wintres woma, þonne won cymeð,

nipeð nihtscua, norþan onsendeð

hreo hæglfare hæleþum on andan.

Eall is earfoðlic eorþan rice,

onwendeð wyrda gesceaft weoruld under heofonum.

Her bið feoh læne, her bið freond læne,

her bið mon læne, her bið mæg læne,

eal þis eorþan gesteal idel weorþeð.

The wise hero must perceive how terrible it will be

when all this world's wealth lies waste,

as now in various places throughout this earth

walls stand blown by the wind,

covered with frost, the buildings snow-swept...

The warriors were taken away by the power of spears,

weapons greedy for slaughter, fate the famous;

and storms batter those rocky cliffs,

snow falling fetters the earth,

the tumult of winter. Then dark comes,

night-shadows deepen; from the north comes

a fierce hailstorm hostile to men.

All is full of hardship in this earthly realm,

the course of events changes the world under the heavens.

Here wealth is fleeting, here friend is fleeting,

here man is fleeting, here kinsman is fleeting,

all the foundation of this world turns to waste.

BL Harley 5431, f.118v

Ac forhwon fealleð se snaw, foldan behydeð,

bewrihð wyrta cið, wæstmas getigeð,

geðyð hie and geðreatað, ðæt hie ðrage beoð

cealde geclungne?

But why does snow fall, cover the ground,

conceal the shoots of plants, bind up fruits,

crush and repress them, so that they are for a time

shrivelled with cold?

So asks the pagan prince Saturn in The Dialogue of Solomon and Saturn, as he seeks answers from Solomon about the nature of the world; but the answer wise Solomon would have given to this question is lost (on a missing leaf in the manuscript). So we don't know.

But another poem, Maxims I, has a promise of something better:

Forst sceal freosan, fyr wudu meltan,

eorðe growan, is brycgian,

wæter helm wegan, wundrum lucan

eorðan ciðas. An sceal onbindan

forstes fetera, felamihtig God;

winter sceal geweorpan, weder eft cuman,

sumor swegle hat.

Frost must freeze, fire burn up wood,

the earth grow, ice form bridges,

water wear a covering, wondrously locking up

shoots in the earth. One alone shall unbind

the frost’s fetters: God most mighty.

Winter must turn, good weather come again,

summer bright and hot.

This is a more positive image of winter: it not only promises that the season will end, will turn again as everything in the year turns, but it actually finds something marvellous in winter itself, in the 'bridges' miraculously formed by the ice. 'Water wears a covering' is like the beginning of a riddle - and in fact there is a one-line riddle in the Exeter Book which reads:

Wundor wearð on wege; wæter wearð to bane.

There was a wonder on the waves: water turned to bone.

'Ice' seems the most likely solution; winter has its wonders, too. And Maxims I asserts that, inexplicable as may be the oppression of winter and the sorrow of human life, God has power to unlock the chains; just as in Beowulf, when the monster's blood melts the hero's sword,

þæt wæs wundra sum,

þæt hit eal gemealt ise gelicost,

ðonne forstes bend Fæder onlæteð,

onwindeð wælrapas, se geweald hafað

sæla ond mæla.

That was a great wonder:

it all melted, just like ice

when the Father loosens the bonds of frost,

unwinds the water's chains, he who has power

over times and seasons.

11th-century calendar from Winchester,

noting the beginning of winter on 7 November (BL Arundel 60, f. 7)

I could go on listing examples all day, but that's probably enough for now to welcome winter. I'm aware that many of my readers live in more fortunate climates, where it's not winter yet (or where summer is just beginning), but here in the south of England it does suddenly feel like winter: a few unusually warm days at the end of October were suddenly laid waste by cold and fog, though not yet by ice and snow. So I'm happy to agree with the Anglo-Saxon calendars that this really is the beginning of winter; in this respect, as in many others, you can't wrong following Bede. It's Bede, of course, who in the voice of a counsellor to King Edwin gives us perhaps the most famous use of winter in Anglo-Saxon literature, which I quoted here recently but will unashamedly quote again, in the Old English translation:

Þyslic me is gesewen, þu cyning, þis andwearde lif manna on eorðan, to wiðmetenesse þære tide þe us uncuð is, swylc swa þu æt swæsendum sitte mid þinum ealdormannum 7 þegnum on wintertide, 7 sie fyr onælæd 7 þin heall gewyrmed, 7 hit rine 7 sniwe 7 styrme ute; cume an spearwa 7 hrædlice þæt hus þurhfleo, cume þurh oþre duru in, þurh oþre ut gewite. Hwæt he on þa tid, þe he inne bið, ne bið hrinen mid þy storme þæs wintres; ac þæt bið an eagan bryhtm 7 þæt læsste fæc, ac he sona of wintra on þone winter eft cymeð. Swa þonne þis monna lif to medmiclum fæce ætyweð; hwæt þær foregange, oððe hwæt þær æfterfylige, we ne cunnun.

"O king, it seems to me that this present life of man on earth, in comparison to that time which is unknown to us, is as if you were sitting at a feast in the winter with your ealdormen and thegns, and a fire was kindled and the hall warmed, while it rained and snowed and stormed outside. A sparrow came in, and swiftly flew through the hall; it came in at one door, and went out at the other. Now during the time when he is inside, he is not touched by the winter's storms; but that is the twinkling of an eye and the briefest of moments, and at once he comes again from winter into winter. In such a way the life of man appears for a brief moment; what comes before, and what will follow after, we do not know."

Dark and cold the winter may be, but this vignette also conjures up one of its best features: feasting in good company, 'the fire kindled and the hall warmed, while it rained and stormed and snowed outside'. Something to look forward to in the 92 days ahead.

This image is from BL Harley 5431 (f.38v), a copy of the Rule of St Benedict made in Canterbury at the end of the tenth century. St Benedict's Rule divides the monastic year into two seasons, summer and winter, which had their different timetables and schedules of prayer; winter began in November, and this section describes the schedule hiemis tempore 'in the time of winter'. Its big initial H is formed from spiky lines which always look to me like brambles, or like bare branches black against the winter sky.

6 comments:

Lovely post - thank you! It annoys me that people insist on the winter solstice as the beginning of winter. Whatever the contemporary astronomical consensus might be, humans experience winter primarily as a climatological phenomenon. To the extent that we experience it as an astronomical event, the solstice is the beginning of winter's end, as the days thereafter begin lengthening once more.

Where I live in central North Carolina in the United States, winter begins much nearer to our Thanksgiving holiday, in the last days of November. I am bookmarking your post to read again when the last leaf has turned brown, and the frost is frequenting the ground.

In the serendipitous way of social media I came upon your fascinating post which I read as the daylight faded outside my window here in the north of Ireland. Thank you so much, especially for including modern English alongside the originals. I shall look forward to further posts.

Is it worth pointing out that, due to to drift between the Julian and Gregorian calendars, the Saxons would have experienced the winter solstice on about December 15th?

Yes, though in terms of counting the days it doesn't seem to make a difference - they considered the date of the solstice to be around the 21st-25th (Bede discusses different ideas about this in 'De Temporum Ratione', and concludes it should be 'a few days before the 25th'). A 92-day season would put midwinter around 22nd December.

jerusalemtojericho, I agree! Psychologically the solstice just has to be the mid-point of winter, not its beginning. Lovely to hear from winter, or not quite winter, from as far afield as Ireland and North Carolina!

I understand that St Lucy's Day was considered roughly the same day as the Winter Solstice, which would have been December 13 under the Julian Calendar.

That was the case in later centuries, but, as I said above, in the early medieval period the solstice was widely considered to fall between 21st-25th December.

Post a Comment